I felt deeply ashamed and miserable. I ran to my father’s room. I saw that, if animal passion had not blinded me, I should have been spared the torture of separation from my father during his last moments. I should have been massaging him, and he would have died in my arms. […]

It is a blot I have never been able to efface or forget.

In 1876 the seven-year-old Mohandas Gandhi moved with his family to Rajkot, where his father had taken up a distinguished position at the princely court. An entrance gate leads into an atrium-like courtyard encircled by the three-winged dwelling in which the family lived since their arrival in Rajkot.

Mohandas had his room in the right wing of the house, which can be seen from the gate. From 1882 onwards, he shared the room with his wife, Kasturbai. The house in Rajkot was the place of two interwoven events that had a formative effect on the young Gandhi: his early marriage at the age of thirteen and his father’s death four years later. Although arranged marriages at such an early age were very common at the time, Gandhi was deeply critical of this tradition in later years.

The unfortunate circumstances of his father’s death had a traumatic impact: Gandhi had been responsible for caring for the sick man but had left him in the care of an uncle in order to see his wife for a moment, during which time his father died. Today the house is a memorial. A permanent exhibition of Gandhi’s photographs and personal belongings is on display in the former living spaces.

At the age of eighteen I went to England. Everything was strange, the people, their ways, and even their dwellings. I was a complete novice in the matter of English etiquette and continually had to be my own guard. Even the dishes that I could eat were tasteless and insipid. England I could not bear, but to return to India was not to be thought of. Now, that I had come, I must finish the three years, said the inner voice.

After Gandhi had left his home province in India at the age of 18 to study in England, he initially had difficulties adjusting to London. He spent the first months studying London society and living like an Englishman. To this end, he invested in violin and dance lessons, took private tuition in English rhetoric, and dressed in the style of an English gentleman. However, this lifestyle was not only costly but also did not accord with Gandhi’s longterm convictions. As a result, he soon dedicated himself wholeheartedly to his studies. In addition, he became a member of the Vegetarian Society, where he gained his first organizational experience as secretary and also wrote for the society’s journal. He also came into contact with members of the Theosophical Society, whose study of the Bhagavad Gita prompted him to devote himself to perusing the text, which he had not read before. The Bhagavad Gita became an important guide in his life. After only two and a half years, Gandhi graduated in law from Inner Temple and was admitted as a barrister to the Inns of Courts in London on June 10, 1891. The Honourable Society of the Inner Temple is one of the four bar associations (Inns of Courts) in London.

Had I been without a sense of self-respect and satisfied myself with having for my children the education in school, I should have deprived them of the object-lesson in liberty and self-respect that I gave them at the cost of the literary training. And where a choice has to be made between liberty and learning who will not say that the former has to be preferred a thousand times to the latter?

11 Albermarle Street, Johannesburg, South Africa

Since 1904 Gandhi’s wife Kasturbai and three of their sons—Manilal, Ramdar and Devdas—were living together again in South

Africa. They first resided in an eight-room mansion at 11 Albermarle Street in Johannesburg.

Their eldest son, Harilal, remained in India. The Gandhis shared the

house with Henry Polak, a close friend and colleague, and Polak’s

wife, Millie, from 1904 to 1906. At home, Gandhi introduced a simple

life and did all the physical household work himself. He even schooled

his own children, but owing to lack of time he was unable to give his

full attention to it.

I had some slight feeling of awkwardness due to the fact that I was standing as an accused in the very court where I had often appeared as counsel. But I remember well that I considered the former role as far more honourable than the latter, and did not feel the slightest hesitation in entering the prisoner’s box.

Courthouse, Government Square, Johannesburg, South Africa

Gandhi defended various Indian men who were part of his

non-violent resistance movement and who had been accused

of political offences. In his pleas, Gandhi not only put forward legal arguments but also focused on moral and ethical considerations. In 1907/8 Gandhi himself stood trial in two political lawsuits

because, in defiance of new regulations, he had refused to register as

required under new legislation. As a consequence he was sentenced to

two months in prison—the first of many sentences to come for civil

disobedience. The site of the original courthouse is currently renamed

Gandhi Square and used as a bus terminal.

The weak became strong on Tolstoy Farm and labour proved to be a tonic for all.

Tolstoy Farm proved to be a centre of spiritual purification and penance for the final campaign. I have serious

doubts as to whether the struggle could have been prosecuted for eight years, whether we could have secured

larger funds, and whether the thousands of men who

participated in the last phase of the struggle would have

borne their share of it, if there had been no Tolstoy Farm.

Lawley, Transvaal, South Africa

In May 1910, Hermann Kallenbach (a Jewish South African

architect and close friend of Gandhi) bought a 450-hectare piece

of land dotted with hundreds of fruit trees only 35 kilometres from

Johannesburg and put it at the isposal of Gandhi’s Satyagraha movement free of charge. After the Phoenix Settlement near Durban, this

was the second experiment in communal living in the countryside. In

honour of the Russian writer Leo Tolstoy, with whom Gandhi was in

correspondence, the farm was named after him.

Tolstoy Farm was mainly intended as a retreat for members of the Satyagraha movement and their families. Together with about eighty other residents, in the period up until 1913 Gandhi and Kallenbach devoted themselves to agriculture, practised handicraft, and experimented with alternative forms of education. Their lodgings were straightforward constructions made from simple materials and built by the people who were to live in them. Their daily life was determined by physical labour, which Gandhi described as very taxing in retrospect, vegetarian nutrition on the basis of subsistence, and a regular practice of praying, singing, and reading from religious texts. They were guided by the maxims of tolerance for different faiths, the relinquishment of personal possessions, and voluntary poverty. Today, there is almost nothing left to remind us of what once took place on this plot of land.

The men and women in Charlestown held to their difficult post of duty in such a stoical spirit. For it was no mission of peace that took us to that border village. If anyone wanted peace, he had to search for it within. Outwardly the words ‘there is no peace here’ were placarded everywhere, as it were.

The little village of Charlestown in Natal, directly on the border

with Transvaal, became the site of the largest Satyagraha action in South Africa initiated by Gandhi. With several thousand Indian contract workers from the mines in Newcastle who had

gone on strike on his advice, Gandhi set out on a 58 km march on

28 October 1913. The aim of the march was to illegally cross the border from Natal to Transvaal and provoke a wave of arrests by the

police. The contract workers’ plan to cross the border was intended

as a protest against discriminatory laws in Natal, which included an

act that only legally recognized Christian matrimony, with all other

marriages declared invalid. Furthermore, extremely high per capita

taxation made it nearly impossible for contract workers to gain permanent residency in South Africa after their five-year contract agreement. Moreover, the Asiatic Registration Act, which had been targeted

by the burning of passes on the forecourt of Hamidia Mosque, was still

in force. The act was accompanied by restrictions on movement, and

even border crossings within South Africa between Natal and Transvaal carried penalties.

Charlestown became the assembly point for all those who were to

join the Satyagraha action as it developed. The marchers camped

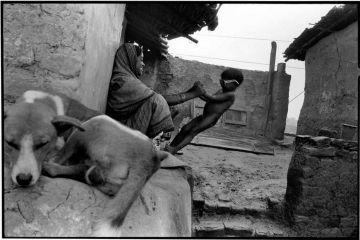

there and were provided with food and a place to sleep by Indian merchants. Today Charlestown seems very rural: a scattering of houses on

slightly elevated ground, mainly rondavels made from clay and corrugated iron, accompanied by small fenced-in plots with some chickens

and a few other farm animals.

I entered the dark waiting-room. There was a white man in the room. I was afraid of him. What was my duty? I asked myself. Should I go back to India, or should I go forward, with God as my helper and face whatever was in store for me? I decided to stay and suffer. My active non-violence began from that date.

Eight days after his arrival in South Africa, on 7 June 1893, Gandhi, as a “non-white” passenger, was expelled from the firstclass section of the train he was travelling on from Durban to

Pretoria and was forced to spend the night in the waiting room at

Pietermaritzburg station. This experience was a turning point in his

life. At that time, Gandhi was not the uncompromising non-violent

resistance fighter for justice but a member of a privileged class whose

pride was hurt and who had been denied his rights.

His subsequent change from a timid barrister to an activist advocating the rights of the Indian minority in South Africa offers an insight into a peculiarity of his personality: he did not just change his

point of view or opinion but his way of life, and he did so with a speed

and consistency that is inconceivable for most of us.

Not least because of its importance in Gandhi’s life, the station in Pietermaritzburg has been painstakingly restored, and the sparse waiting room is still used by passengers in transit. A simple portrait serves

as a reminder of a night when a decision was made that would lead to

more than twenty years of committed work in South Africa.

That day in Champaran was an unforgettable event in my life and a red-letter day for the peasants and for me.

In 1917, Gandhi’s Champaran campaign took him to Bihar. There

he successfully supported the local peasants in their fight against

the compulsory cultivation of indigo plants imposed on them by

British companies. As a rule, the peasants had to lease their acreage

from the British owners, and the obligation was a threat to their livelihood. After Gandhi’s return from South Africa, this was the first of

many Satyagrahas in India. The cities of Motihari and Bettiah were

the geographical centre of this resistance. On 17 May 1917, Gandhi

arrived by train at Motihari railway station, where he was received

by thousands of hopeful peasants, just as he had been in the city of

Bettiah.

The world outside Champaran was not known to them. And yet they received me as though we had been age-long friends. It is no exaggeration, but the literal truth, to say that in this meeting with the peasants I was face to face with God, Ahimsa and Truth.

Murli Bharwa was the home of the farmer Raj Kumar Shukla, who approached Gandhi and took him to Champaran

personally to aid the local tenant farmers in their struggle for survival. During his stay in the region, which lasted some six

months, Gandhi visited dozens of villages to find out about the plight

of the indigo peasants. He discussed their sufferings with the owners

and managers of indigo factories. In the end Gandhi’s Satayagraha

activities were successful: in October 1917, the British government accepted the recommendations of the Champaran committee to terminate forced indigo cultivation and with it the reason the peasants were

being exploited.

Of course Visva-Bharati is a national institution. It is

undoubtedly also international. You may depend upon

my doing all I can in the common endeavour to assure its

permanence. I look to you to keep your promise to sleep

religiously for about an hour during the day.

(Gandhi to Tagore)

Since his return to India, Gandhi had visited Shantinketan periodically and called Tagore’s domain his second home. Tagore asked

Gandhi to help secure the continuation of Visva-Bharati (communion with the world) after his death, which Tagore had compared to a

ship laden with his most precious possessions. In contrast to Gandhi’s

Vidiapith University with its emphasis on Indian traditions and national values, Tagore was convinced by his idea of international exchange:

“So under Visva-Barathi we render our homage by weaving garlands

with flowers of learning—gathered from all quarters of the earth. To all

devotees of truth, both from the West and from the East, we extend our

hand with love.”

Currently academic teaching is partly done outdoors, as the classrooms laid out in circles under trees demonstrate.

My error lay in my failure to observe this necessary limitation. I had called on the people to launch upon civil

disobedience before they had thus qualified themselves

for it, and this mistake seemed to me of Himalayan

magnitude. […]

I realized that before a people could be

fit for offering civil disobedience, they should thoroughly understand its deeper implications.

After the First World War ended, Indians hoped for an acknowledgement of their involvement in the war alongside the British and the re-establishment of their civil rights, which had

been restricted within the framework of martial law. Their hopes were

gravely disappointed by the so-called Rowlatt Act, which entrenched

this situation rather than eliminating it. Gandhi was no longer willing to support the British government in India as he had done during

the war. He found himself forced to organize resistance against the

government. He called for hartal on 6 April 1919 which provoked the

colonial rulers nationwide.

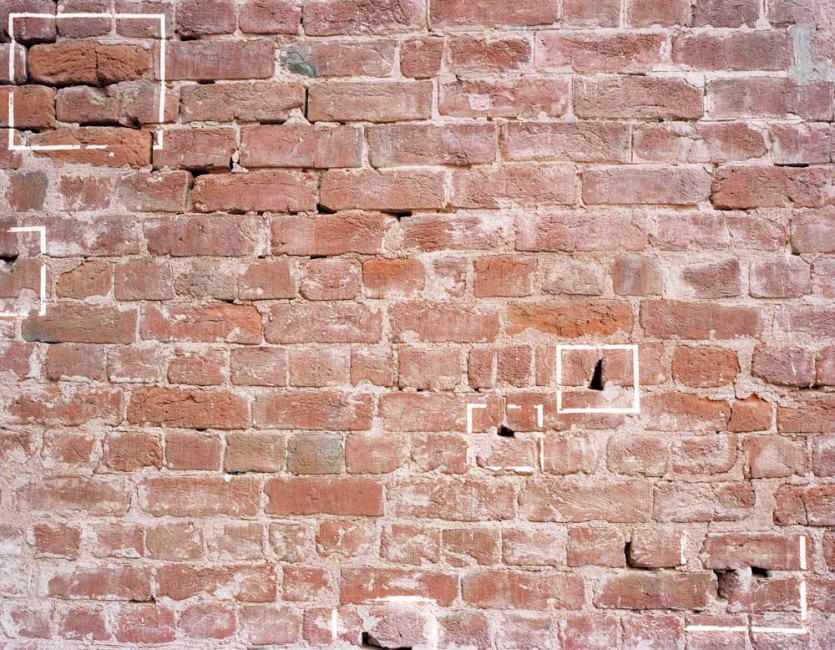

This prelude to civil disobedience turned violent at times—a striking breach of the principles of Satyagraha. Gandhi considered it a serious error to have instigated civil disobedience in a people who were obviously not mature enough in his view. The most brutal reaction to the nationwide unrest came from British General Reginald Dyer. Without warning, he ordered his soldiers to shoot into a crowd of Indian demonstrators, who had gathered in a small park in Amritsar with no way out. Almost four hundred people died in this massacre on April 18, 1919 and three times as many suffered gunshot wounds. Gandhi called off the Satyagraha on April 18 and went on a three-day fast of repentance.

Today the place is a memorial. Some bullet holes are still visible in the walls surrounding the park and are marked for visitors.

From the very start I set my face against taking advertisements in these journals. I do not think that they have lost anything thereby. On the contrary, it is my belief that it has in no small measure helped them to maintain their independence.

The Indian Opinion, published by Gandhi, was an important

voice in the fight to combat the discrimination against Indians in South Africa. Having realised the impact of journalistic

activities, Gandhi began producing Navajivan in 1919, a journal published in his mother tongue, Gujarati. Further periodicals followed:

Young India was a weekly journal in English, published by Gandhi

from 1919 to 1931, which he primarily used to promote his ideas

about Indian self-government. Since his imprisonment in Yerawada

Jail, Gandhi had published Harijan, a journal that focused on economic and social problems—he continued the journal until the end of

his life. Issues of Gandhi’s periodicals are collected in the archives of

the Navajivan Publishing House in Ahmedabad

My inner voice tells me, you should not witness this senseless slaughter. If people refuse to see what is as clear as the light of day and pay no heed to anything you say, does it not mean that your days are over?

Noakhali, Chittagong District, Bangladesh

In November 1946, Gandhi travelled to Noakhali, now in Bangladesh, to help end the horrific massacres in the area, which had

taken place in anticipation of Indian independence and the impartition the country. At the age of seventy-seven, Gandhi went on

an arduous march for peace through Noakhali, a rather inaccessible

region located in the Ganges Delta. The small village of Sadhurkhil

was the destination for the first part of the march, which had started

in the village of Srirampur and was to end in Haimchar.

** Mohandas Gandhi quotations courtesy Navajivan Trust, Ahmedabad