On September 2 last year Jebanti and her two-year-old

daughter started the longest journey of their lives. In Kumbharigan, her

village in Odisha’s Kandhamal district, a place of aching beauty ringed by the

Eastern Ghats, in the stranglehold of poverty since forever, hope was precious.

Not yet 18, Jebanti could afford it; she had the impossible optimism of the

young. Her brother Jeetendra Uthansingh, one of 11 siblings, came with her.

They took an overcrowded autorickshaw from Kumbharigan to Brahmingaon, a

village masquerading as a town, about four kilometres away. In its lone street

they waited for a bus to Brahampur, the nearest railhead on the Chennai-Kolkata

route. There was room inside, they didn’t need to travel on the roof or hang by

the door like dozens of others. Almost four hours and 120 kilometres later,

they reached the station.

Jeetendra bought unreserved tickets for all of them to Chennai. They got into the Bhubaneswar-Rameswaram express, the first train they found, squeezing inside the packed compartment. The next 19 hours felt unbearably long for Jebanti. It was only the third time she was in a train. Jeetendra played with his niece, chatted up fellow passengers and did everything he could to distract himself from the truth he was hiding.

Next morning, weather-beaten and weary, they got down at Chennai Egmore. They transferred to Chennai Central. Soon they were in a general compartment of the West Coast Express to Mangaluru. Jeebanti was getting anxious now. She hadn’t heard from her husband, Sanjay Pradhan, for over three days. She hadn’t spoken to him for over a week. All she knew was that he had fever. The second eldest of her brothers, Mithun Uthansingh, had last spoken to Sanjay three days earlier. He was at the government hospital in Thrissur and delirious. He had wanted to see his wife and daughter, “one last time”.

They got down at Palakkad in the evening and Jeetendra enquired about the train to Aluva, a town on the outskirts of Ernakulam. Its small station is often the first stop of thousands of migrants to Kerala. They took a train sometime after 9 p.m. Jeetendra started feeling uneasy as their journey came closer to the end. He sat still when he wanted to pace up and down the coach. He couldn’t give his sister any hint. It was past midnight when they neared Aluva.

Amid the lights she could see from the train window—so different from the darkness and silence of Kumbharigan—and the cars that went by, Jebanti remembered her first journey here more than three years ago. She had stars in her eyes then, a sweet trepidation about the future, and a promise of a life beyond her dreams. This time it was different. Sanjay was not with her. As they got down at Aluva, Jebanti felt a sense of despair. Jeetendra haggled with an auto driver and finally paid ₹600 to go to Angamaly, about 13 kilometres away, where Sanjay stayed in a room shared with many others. It was around 2 a.m. by the time they reached and found a cheap hotel. After almost 35 hours of travel, they lay down and slept.

In the morning, Jeetendra told Jebanti they would not go to Thrissur but to the Government Hospital, Ernakulam, where Sanjay was being shifted. He didn’t tell her Sanjay was dead, that he had brought her so that she could see him one last time. She had to see his body to believe he was dead, the family had decided. Sanjay was his friend, a brother almost, and as he fought back his tears, Jeetendra thought his sister’s life was over. Married at 15, widowed at 18. A child in between.

***

S

anjay was a migrant, crisscrossing the country for a stab at the life of three meals a day and a house of his own—the ultimate elusive dream of millions of Indians. He died an unremarkable death in a Kerala hospital. In the ordinariness of his life and the journeys that took him to the ends of the country lies the India of migrants—it exists in the general coaches of long-distance trains and in countless shantytowns scattered across the land.

Indians are on the move. The last 20 years have seen an immense movement of people over great distances in search of work, overpowering barriers of caste, religion and language. Various estimates exist about the number of migrant workers in the country. They range from 55 million to 125 million. The 2016-17 Economic Survey analysed railways passenger data for long-distance trains and estimated an annual interstate migration of nine million people between 2011 and 2016. The survey also estimated interstate migrant population at 60 million and inter-district migrant population at 80 million. These numbers are much higher than census and other government estimates. The 2001 census pegged the annual flow of migrants at 3.3 million. Provisional data from the 2011 census suggests that the total may be in excess of 125 million. Its definition of a migrant as a person enumerated at a place different from their place of work does not fully capture the complexity of migration in India.

India is fast becoming two nations. One is the richer south and west along with some smaller states. The other is the populous, poorer north and eastern states. This divergence started in the Eighties and India is an outlier in global terms: Poorer states haven’t grown faster from a lower base on economic indicators. While there is some convergence in health indicators, the gaps between fertility rates and infant mortality rates are an order of magnitude wide between states like Kerala and Tamil Nadu, and UP and Bihar.

Labour corridors like Ganjam-Surat, Guwahati-Delhi capture this divergence, the movement of labour from poorer to richer regions. Its also reflected in the size of the India’s growing remittances market. The 2016-17 Economic Survey estimated the domestic remittance market exceeded ₹1.5 lakh crore per annum. Remittances out of Kerala are estimated at ₹17,000 crore.

***

J

eetendra wanted to know what to do next. He called home to Mithun who asked him to get in touch with a pastor. Their eldest brother Arun, working in Kerala at the time, was already in Thrissur to get the body shifted to Ernakulum. The Uthansinghs are church-going folk, and they sought the help of the Roman Catholic bureaucracy in the biggest crisis that faced their family.

George Mathew entered their lives then. A short, thin man with crooked teeth, thick glasses and an easy smile, George is that rare thing: an uncorrupted activist. He had heard of Sanjay’s case from a pastor in Perumbavoor—a migrant hotspot in Kerala, that has Odia service in some of its churches. Part of the People’s Union of Justice, a politically unaffiliated alliance of activists in Kerala, Geroge did what he always does—jump into the case.

Jeetendra and Jebanti made their way to Kalady where George lives. He started working the phones, arranging for the transport of Sanjay’s body from Thrissur to Ernakulam. He would do everything to make the family’s one wish come true. They wanted the body sent home, and Sanjay to be laid to rest in the village graveyard. Another day passed before the transfer could take place. That night Jeetendra, Jebanti and her daughter stayed at George’s place. By then even though she had not been told, Jebanti couldn’t escape the grimness around her. She was getting frantic. Sanjay’s phone wasn’t working and her brother wouldn’t say anything reassuring. She put her daughter to bed and cried herself to sleep.

More recent research by the Centre of Migration and Inclusive Development (CMID), a Perumbavoor-based policy think thank, puts the interstate migration in Kerala at 35-40 lakh. It built on the Gulati estimates and factors in other modes of entering the state like buses from neighbouring regions.

Kerala is a paradox in many ways. It has low female labour

workforce participation, a high rate of unemployment at 12.5 per cent (the

national rate is 5 per cent), and a population that doesn’t do low-skilled

labour-intensive jobs. The biggest contributor to the state economy is

remittances from abroad, 35 per cent of the state’s GDP at ₹90,000 crore.

In this soup swim the migrants. Almost every low-level job in every sector is

now held by a non-Malayali. Labourers from Assam, West Bengal, UP, Bihar and

Odisha are the levers of the state. They tap the toddy, make the beef roast in

restaurants, collect the sap in the rubber estates, break stones in the

quarries, build houses, set tiles, lay roads, tend gardens, glue plywood,

operate sawmills, and fish. An army of mostly men, speaking in many tongues and

a smattering of Malayalam are the uncomplaining beasts of burden in the state.

***

O

n the evening of September 4, an ambulance from Thrissur arrived at the General Hospital, Ernakulam, carrying Sanjay’s body. Once George informed them, Jeetendra, Jebanti and her daughter made their way to the hospital. The morgue is a small squat red-and-white building in the complex. A narrow door on the left is the entrance. Outside is a small row of rusting black metal chairs. By the time they arrived, George and Arun were there. It was the moment of truth, and Jeetendra wished he was somewhere else.

“If I had not kept her in the dark she would have been in no condition to come. And we really wanted her to see him one last time. It was a terrible load to bear and I still can’t shake it off,” he said.

As she stood outside the morgue, Jebanti felt she was being sucked into an abyss. This small building, it didn’t look like the big hospital of a big city, so what was Sanjay doing here, she thought. Why was he not admitted in the multi-storey hospital blocks left and right of her? Jeetendra finally told her, his voice cracking, tears breaking the dam: “Sanjay’s body is inside, go see him.”

It didn’t register. She was stunned, kept staring into the wall of the morgue. Jeetendra told her again to go inside. She didn’t want to go. Finally, the brothers pulled her inside the narrow corridor with dull yellow walls at the end of which on the left was the cold room where Sanjay’s body was kept. Jebanti caught a glimpse of Sanjay’s shock of curly hair from the door and broke down. She ran out. Her wails filled the air outside. Her daughter panicked on seeing her. The brothers gathered around her, fighting their own tears, consoling each other. George knew of a building that was rented by workers from Odisha not far from the hospital and he suggested they go there and stay till he found a way to send the body home.

What happens when a migrant worker dies? It depends on the

manner of death. If it is in the course of employment, the employer tries to

hush it up, sometimes quickly arranging a funeral and offering the lowest

payout he can. The employer doesn’t want labour officials involved, because

then a file is created, and like all government files it becomes fish bone

stuck in the neck, forever. No body, no case, no file. Life goes on. That is

optimum solution. S. Nazar Ali, assistant labour officer in Perumbavoor, says,

“We have only two cases of death reported in the course of employment in the

last three years. In one case, a compensation of ₹5 lakh was paid. It is a duty

of the employer to report accidents and injuries to us. We come into the

picture only once we are informed. If we do not know, what can we do?”

This in Perumbavoor, where more than 1.5 lakh migrant workers live and work, the hub of the plywood industry, a sector not immune to accidents. In some cases in Kerala, to keep things quiet, employers have sent bodies back as far as coastal Andhra Pradesh by ambulance, activists and workers say.

There are no estimates of the number of migrant worker deaths, natural or accidental, in the state. There are no numbers at the national level either. There are 120 million migrant workers in India, nine million workers migrate interstate annually. Researchers in Kerala, based on anecdotal evidence, say at least four to five workers die every day. That’s about 1,500-1,800 deaths a year in one state. In many cases families know only after the funeral. According to 2015 World Bank data India has a male adult mortality rate of 212 deaths per 1000 of population, adult being defined as between the ages of 15-60. For migrant workers, especially those in hazardous occupations like quarrying, the rate is likely to be higher. When workers from Bangladesh with irregular papers die they are silently cremated, often at the behest of friends and families who don’t want unwelcome government attention.

When a worker dies of disease, as Sanjay did, it is neither a labour matter nor an employer issue. It is up to the family, often a great distance away, to arrange the last rites.

“It costs ₹30,000- ₹35,000 to repatriate the remains by flight, hardly any money for the government. Why can’t states like Kerala with huge numbers of migrants have a formal policy on repatriation? It is the humane thing and provides succour to the families,” said George. It is one of the many causes he is fighting for. In the absence of government help, George says, grief-stricken families are fleeced by touts who negotiate with the employer and take money from the family. They charge ₹50,000- ₹70,000, exploiting the family at its most vulnerable.

Time was running out. Four days had passed since Sanjay’s death and there was pressure from the hospital to take the body. The longer it took the less the chance of a funeral in Kumbharigan. George started sending messages on media WhatsApp groups, and even got a few journalists to visit Jebanti and her brothers. He called the Collector’s office in Kakkanad and fixed an appointment for the family. He started calling the labour minister’s office in Thiruvananthapuram, and kept at it till he got somewhere. Because this is Kerala and because George is tenacious, something clicked. The labour ministry sanctioned funds for the repatriation, the family met the collector on September 5 and he promised help. Finally, they could think of going home.

***

M

igration into Kerala began in waves, the first between 1961-1990 from the poorer border districts of southern Tamil Nadu and Karnataka. After that the floodgates opened, with new labour corridors from the north and northeast, while Tamil Nadu continued to supply seasonal labour. Most of the labour coming in is from places which are at risk from floods, droughts, and internal conflict coupled with poor industrialisation. “The profile of a migrant worker is a single male, 15-35 years old from the tribal, SC or Muslim community,” says Benoy Peter, the tall soft-spoken director of the Perumbavoor-based Centre for Migration and Inclusive Development (CMID).

Last year Benoy and his colleague, CMID’s programme director Vishnu Narendran, produced a report, “Gods own workforce—Unravelling labour migration to Kerala”. In 2016-17 they travelled across all of Kerala’s 14 districts and conducted extensive interviews across sectors. They found migrants from 194 districts of 25 states and union territories working in Kerala. Nearly 60 per cent of the source districts are in the north and northeast.

They identified 12 migration corridors that have evolved in the last two decades spanning 2,300-3,500 km, connected by rail. Of the 12, Nangaon (Assam)-Kollam is the longest at 3,500 kilometres. Eight of the corridors originate in West Bengal, three in Assam and one in UP. According to the CMID report, the first wave of migration from Assam was of plywood workers in the mid-Nineties. A Supreme Court order banning forest-based plywood was the trigger. This left thousands of skilled workers—mainly Muslims—jobless and drove them to Kunnathunadu taluk in Ernakulum district.

Some of the reasons migrant workers find Kerala an attractive

place are: highest wages in the country, relatively less exploitation, better

conditions of living than, say, Mumbai, and less harassment by authorities. It

hasn’t however, been smooth sailing. There is a fear of the migrant in many

sections of the society and the media fans a discourse where any crime committed

by a migrant worker is amplified and debates and discussions are held on it.

There have been instances of violence against workers aswell as crimes

committed by them. The most notorious is the Jisha case, of 2016 where a worker

from Assam was sentenced to death for the rape and murder of a 30-year-old law

student. It spawned a sea of anti-migrant sentiment in the state, helped by a

charged media discourse. In May 2016, a migrant worker just arrived in Kerala

was lynched near Kottayam and left to die on suspicion of stealing.

A narrative exists that says migrants vitiate Kerala’s progressive atmosphere, that they are less civilised and unclean. A senior economist who has done research on Kerala’s migration and is sympathetic to their case says, “Look, I will not rent them my house. They have poor hygiene and don’t care about cleanliness.”

There’s also the exaggerated fear of illegal migrants from Bangladesh, many of whom police suspect may end up forming sleeper cells of Islamist groups. The number of Bangladeshi workers is not known, though anyone who speaks Bengali is a potential suspect. CMID’s report says undocumented workers from Bangladesh pass off as being from Assam or West Bengal.

“Kerala needs the workers more than the workers need the state,” says Benoy, “The population here has been below replacement levels since 1987, the Malayali has a strange addiction for white-collar jobs, and nothing will work here if workers don’t come. Labour can flee to other markets. It is in the interest of the state to treat its migrants well.”

I

n 2001 Sanjay Pradhan first entered their lives in Silvassa, Dadra and Nagar Haveli, the small wedge of land between Mahrashtra and Gujarat. Three of the Uthansingh brothers, including Mithun and Jeetendra were working as casual labour in a tubelight factory. It was an early pit stop in the migrant life for them. They were timid and didn’t have many friends. Jeetendra says many nights he went to bed in tears, punched in the gut by an unbearable loneliness. No matter how hard they worked, how much they earned, they remained poor. One day they noticed a boy, small and thin, working there: Sanjay Pradan. He didn’t look older than 10, but worked as well as anyone else. They got talking and soon started having meals together. Jeetendra was a few years older, and Mithun, who was an adult, was more like a guardian.

“He would always clam up when we asked him about home and family. He just said he was from West Bengal and had run away because of a fight with his father. He had got into a train going to Gujarat. Somehow he reached Silvassa and started working here,” said Jeetendra. But the boys would not give up. Over the years they kept asking him about family. They would crack his stony silence but not break it. Some details would slip by. One day he would tell Jebanti he was from Howrah, and when he ran he got into the train because the station was close to his home. He would tell Mithun some day that he had an elder brother he liked and a stepmother he didn’t. That he would once in a while call his brother. Once, after he had married Jebanti, the brothers got him drunk hoping he would open up. After many rounds, they started interrogating him. Sanjay knew what was happening, he just pretended to pass out.

Months after he first met him, Mithun was going home and he took Sanjay along. “He was barely a boy, didn’t even have the beginnings of a moustache. I thought he should have a home, a place he could go to. So I brought him with me. My father accepted him as one of us from the beginning.”

Thus Sanjay landed in the house of Marko Uthansingh in Kumbharigan, a village of decaying huts and filthy lanes, embraced by forests and hills, where the church is in ruins and the graveyard overrun by weed, two places that would ultimately mark his life.

T

he Uthansingh brothers, five of the six, and Sanjay travelled huge distances for work. They were in Silvassa three to four years, then Sanjay moved to Diu for a short while. Next stop was Goa, where Sanjay could work his dream job, a helper in the kitchen of a beach shack. The brothers got odd jobs that came their way at the labour markets. They didn’t like Goa much, and moved further south to Kannur in Kerala. They did all kinds of odd jobs here. Sanjay worked at a stone quarry for three years around this time, a physically demanding job he didn’t like. He was set on working in the hotel sector, becoming a cook. After four or five years in Kannur, brothers are fuzzy about dates and years, Sanjay moved south to Palissery. For the next five years he worked in hotel kitchens around Paliserry and Angamaly, learning the trade. He would often take the train to Kannur to meet Jeetendra and the others. “He was like a brother to us. He would come when he got leave,” said Jeetendra. “Ek thali me khaate the hum log (We ate from the same plate).”

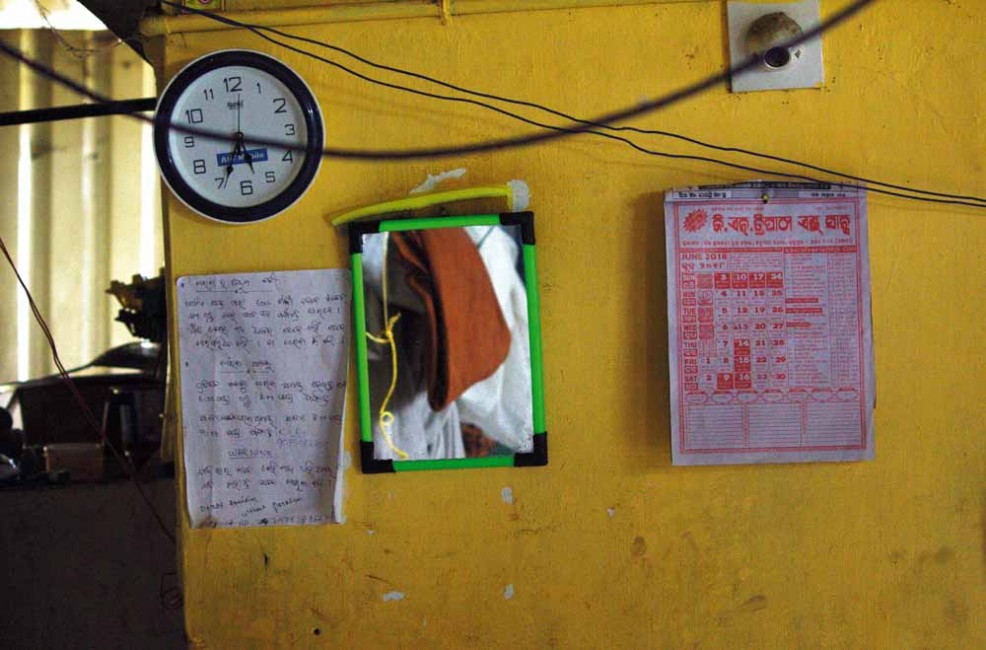

It is a monsoon dusk, darker and heavy with rain, at the Bengali Colony in Kandathara in Perumbavoor, an area of many plywood factories. The narrow road has a few shops, incomplete buildings and a big triangular blue two-storied dormitory for workers of the nearby factory. It’s past six and the place is shrugging off the coils of a dead afternoon as the workers return from work. The colony is soon abuzz, beedi smoke fills the air, makeshift lottery shops appear, the butcher opens up, mobile phones start playing music, and its three hotels spring into action.

The largest population here is from West Bengal’s Murshidabad district, divided into Hindu and Muslims with separate rooms and hotels. Young and middle-aged men from neighbouring villages live cramped together—eight to ten in a small room. The colony hosts masons, plywood workers, tile setters, road builders, and helpers, those with lesser skills who can work in any sector. Kerala was not the first stop for many of them. Inside the Hindu Hotel, a dimly-lit long and narrow room with rough plastered floor and walls, the India of the migrants is being discussed.

“Delhi is cheap, but bad air and bad cops, and you never get the full money”, “Bombay is good pay, but you sleep on the streets”, “Surat has too many Odiyas and Bangladeshis”, “Alang paid well but pollution people closed it”, “Nagaland is good, Bangla works there, and work stops late afternoon”, “Agra is terrible, so bad that I didn’t even see the Taj Mahal”, “Kerala is the best, cops don’t beat you and it has the highest wages”, and so forth. The migrant’s India is a separate geography. It has its own atlas that workers carry in their heads, a directory of construction sites, factories, ship-breaking yards, quarries, plantations and shantytowns.

***

O

n the evening of September 5, 2017 Anil Kumar came to the room he shared with 20 others at the top floor of Rajan Building in Ernakulam and saw a petite young woman with a baby crying at a corner. She was standing next to the shell of a television that now served as someone’s storage. She was partially hidden by the clothesline, but her sobs were loud and he could hear her gasp. He went about his business.

“When you share a room with 20 people, someone is always coming, and someone will always cry,” he said. When he returned after a smoke and adda with his friends at the tea shop, she was still sobbing. He asked around and someone told him her husband was dead, and that she was here to take his body home. He later found out that she was just a few kilometres from his village in Odisha’s Gajapati district. In fact, all the tenants of the terrace-room were from villages in Gajapati district. A spontaneous kinship began to form in the room. The men offered help, some even went to the hospital with Arun, and some played with Jebanti’s daughter.

Jebanti, though, was lost. She could make no sense of Sanjay’s death. Everything was happening too fast for her. She had met the collector in the day, a meeting she barely remembers. George had told her that tomorrow she would be going home. Sanjay would get a funeral in Kumbharigan.

Sanjay had been coming to Kumbharigan for a decade. Marko Uthansingh, Jebanti’s father now thought of him as a son. He was one with the brothers, and people in the village knew him as part of Marko’s household. In between jobs, whenever he wanted a break, Sanjay would head home. Sometimes he would stay a couple of weeks, sometimes a month and then return. He would help Marko tend his small patch of land by the church. Marko grew turmeric. Unknown to Marko and the brothers, Jebanti and Sanjay had become close. No one suspected, but they knew that their relationship wouldn’t go anywhere in the village. Jebanti was not yet 15 when she and Sanjay ran away from the village. He took her to Angamaly and they started living together. Sanjay worked at a hotel and was good at his job. “He was a karigar. He could make mithai and also work the tandoor,” Jebanti said. “The seth loved him, and paid him well.”

Their elopement caused a stir in the village and in Marko’s home. “I brought him home, we loved him as a brother and he betrayed us like this,” Mithun said.

Jeetendra said, “They fell in love, what can you do about it? We weren’t angry for long.”

“I thought of him as a son anyway, so I forgave him,” said Marko. Others in the village blamed him for letting an outsider enter his home.

Jebanti and Sanjay spent six to seven months in Angamaly. It was the happiest period of her life. She had never seen a town before, never lived on her own, never been in love before. She was wonderstruck with everything around her: big cars, big shops, a meal at a restaurant. On Sanjay’s day off, she would dress up and they would travel to nearby places and sometimes eat an ice-cream.

When they returned to Kumbharigan, tempers had cooled. They were welcomed. Marko even helped make a small house for the couple, right opposite his own. After a few weeks, Sanjay left again for Palliserry but this time Jebanti stayed back. “He would come every few months. He always sent money for expenses, about ₹7,000-8,000 a month. I could live well,” said Jebanti. A little more than a year later, their daughter was born. They named her Sanjita, after her father.

Last August Jebanti fell sick, and Sanjay came home for a month. He left at the end of August to return in three to four months with some money. He complained of headache when he got got down at Aluva. The first day back at work he had high fever. On August 30, the Angamaly hospital referred him to the government hospital at Thrissur. Two days later he was dead of cerebral malaria.

***

I

n the front part of the mortuary at General Hospital, Ernakulam is the autopsy room. Sanjay’s body was placed on one of three steel slabs. By the side of slab is a small table with blue and orange buckets, sponge and other tools of the trade. Two mortuary helpers cut open the body under the supervision of Dr. Biju James, the district police surgeon. All internal organs were removed, placed inside a sealed plastic bag and kept in the body cavity. The body was then pumped full of chemicals that would stop decay. It took about an hour, and at 12:30 pm on September 6, 2017, Sanjay’s body was embalmed. A certificate signed by Dr James was issued, it said the body “will remain in a state of preservation for three days and will be source of infection or hazard to the public.”

At the back of the mortuary at the end of the narrow corridor is Dr. James’ office. A jovial man with a handsome moustache, Dr. James said, “To give a safer number, I think about 25-30 bodies a year of migrant workers a year are embalmed at this hospital.” It is a practice he doesn’t endorse.

“I think it is a waste of resources. The chemical used is expensive, even hazardous, and it is not environmentally sound because the body takes a long time to decompose after that. While I understand the grief of the bereaved, what is wrong in cremating or burying here? Money can be saved.” The embalming fee is ₹10,000. “The dead deserve respect, but I stand by the living when it comes to distribution of resources,” Dr. James said.

Geroge had arranged a reinforced coffin for the journey. He had booked flight tickets for Jebanti, Sanjita and Arun, and completed the paperwork for the transport of Sanjay’s body. In the evening Arun, Jebanti and her daughter travelled in an ambulance with Sanjay’s body to Kochi airport. At 11 p.m., they took an IndiGo flight to Bengaluru and landed past midnight. They spent the night at the airport and took a morning flight to Bhubaneswar.

The first time Jebanti entered the airport at Kochi, she was awestruck. She had never seen a place like that. Who were all these purposeful people with fancy suitcases, and where were they going? She didn’t understand a word of Hindi or English the airhostess spoke. Finally, one of them buckled her in. She thought she would die when the plane started its take-off run. When it was airborne she expected it to fall out of the sky anytime. If Kochi was a shock to her system, Bengaluru airport, with its expanse of glass and steel, left her dizzy. By the time she reached Bhubaneswar, she was less afraid of the planes.

It was around 9 a.m. The district labour officer from Phulbani had arrived with an ambulance to take them and Sanjay back to Kumbharigan. The Ernakulam collector’s office had followed up with the administration in Kandhamal. This was the last leg of her journey.

She sat at the back of the ambulance as it started for Kumbharigan. In between they got lost in an attempt to take a short cut. It was evening by the time they reached the village. Sanjay’s body was placed in the courtyard of Marko’s small house for a day. Jebanti kept vigil in the night. She thought about all of Sanjay’s dreams that would never come true now.

“He wanted to open a hotel of his own. Make money, build a bungalow in the village and live in comfort,” she said. Since Sanjita’s birth, his dreams included her. “He wanted her to study all the way till college. He wanted to give her a grand wedding. I don’t know how any of this will happen now. I am now dependent on my father and brothers,” she said.

***

T

he next day they buried him in a corner of the graveyard, a short distance from home. Nine months later it is still a fresh grave, the only one visible in the graveyard, its mound of earth not yet one with the ground, the soil not yet vanquished by weeds. At its end stands a crooked wooden cross. Its withering black lettering states: “Sanjay Pradhan, 1-09-17”.

“We dug a deep grave and laid him there. I called the Father to conduct prayers, but he never came,” said Mithun. “It was essential that we brought his body home. Jebanti would have no face left to stay in the village otherwise. They would all have said an outsider married her, had a child with her and then abandoned her.”

Jebanti has explained everything to Sanjita. “She saw his body in the courtyard, she was with me all the time. She knows baba is buried there,” said Jebanti at Sanjay’s grave. She wants Sanjita, the silent girl with big black eyes, to know about her father’s life:

Sanjay Pradhan, a man from Howrah, who travelled thousands of kilometres across half the country to earn, the worker in the quarry, the setter of tiles, the maker of mithai, the master of tandoor, all of 25 and in eternal rest at Kumbharigan.