The term love

failure has a tragicomic resonance unmatched by any other phrase

bequeathed by cinema to language. Growing up in Madras in the Nineties and

watching whatever Doordarshan provided, I came to associate it with T. Rajender

contorting his hirsute face into a tortured expression, with Charlie Chaplin’s

tramp until he caught a break in City Lights, with Tom’s desperate

overtures to Toodles Galore, with Popeye and Bluto vying for Olive Oyl, and

eventually with one of my puppies making aching noises as he stared across the

road at a streetie sunning herself. But take away the quirky and we’re left

with violence, destruction, death.

When IT professional Swathi S., 24, was murdered in the presence of witnesses at Chennai’s Nungambakkam railway station on June 24, it shook the city. Her killer Ramkumar had stalked her for months. In a confession leaked to the media, he is reported to have said, “I spent a lot of time on Facebook. That was how I met Swathi. Then I got in touch with her on WhatsApp. I used to text her often, and she would reply. After this, I wanted to meet her and that was why I went to Chennai. I stayed in a Choolaimedu mansion near her house. I would follow her on her way to work. I introduced myself. As I was a Facebook friend, she was amicable.

“After a few days, when I told her I was in love with her, she walked away silently. She had many friends. She would talk to them often. I did not like this. I told her she must only talk to me. She told me off. As I pestered her constantly, she would ask her father to accompany her to the railway station. Twice, I waited at the railway station to talk to her. Once, she told me I looked like a thevangu (slender loris) and asked me not to talk to her again. At the time, I wanted to tear her lips. But because of my love for Swathi, I walked away. On 24th [June], I begged her to reciprocate my love. She refused. Then I attacked her with the sickle.”

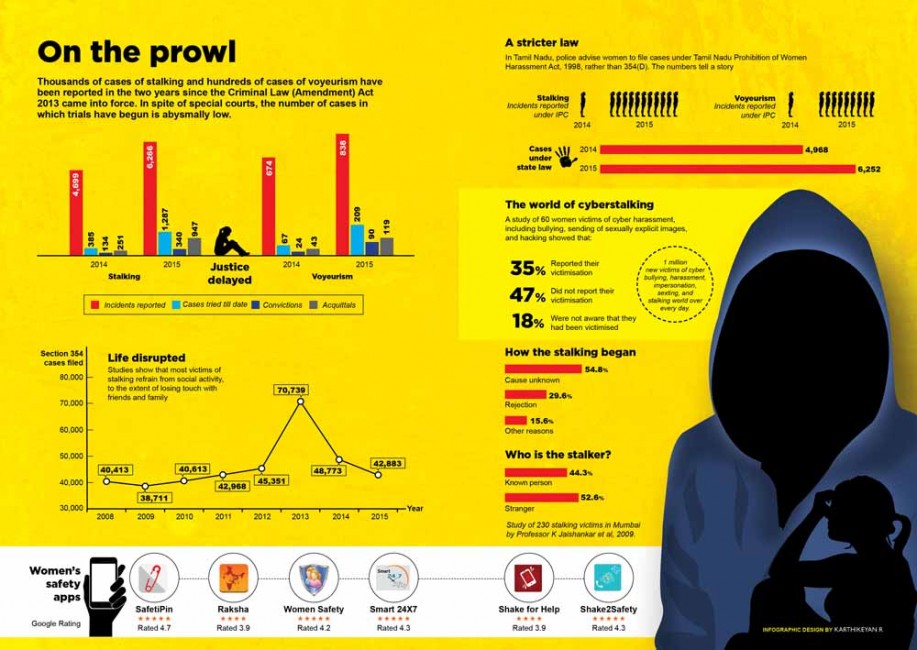

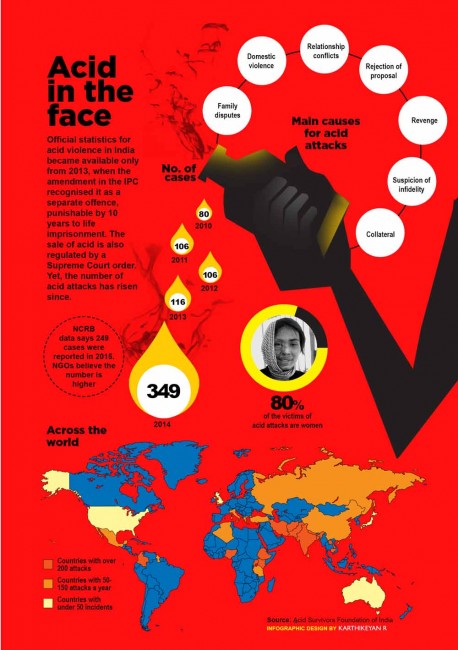

An acid attack occurs once every 16 hours in India. Every 24 hours, the police register 17 cases of stalking and two of voyeurism. Studies estimate the percentage of reported crimes against women to be between 8 and 14 of actual crimes committed.

The raw statistics of stalking are frightening enough. An acid attack occurs once every 16 hours in India. Every 24 hours, the police register 17 cases of stalking and two of voyeurism. Studies estimate the percentage of reported crimes against women to be between 8 and 14 of actual crimes committed. By the time you read the last sentence of this article, six women could have been harassed by a stalker.

The anecdotal evidence is even more disturbing.

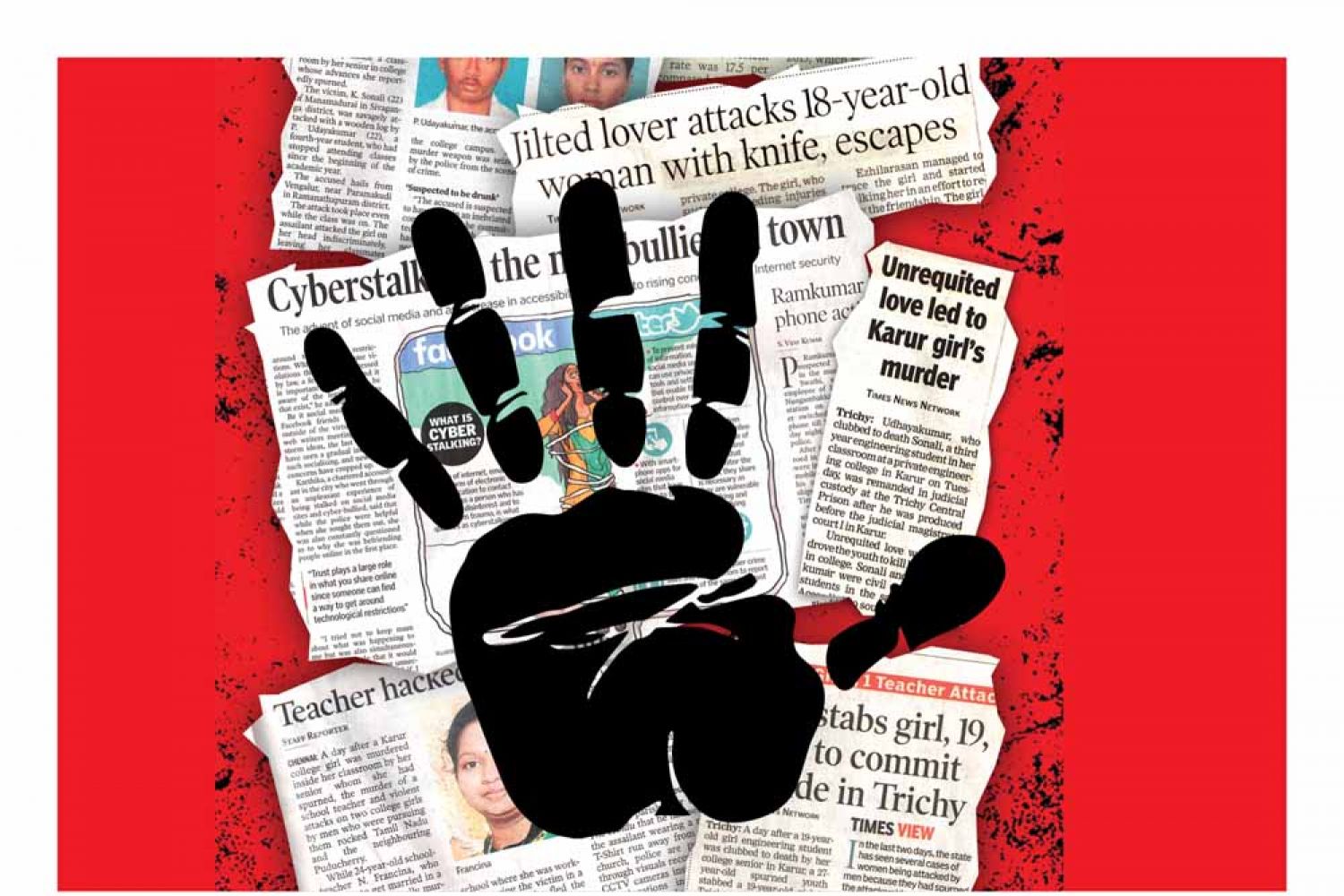

As news channels across the country followed the Swathi murder investigation, stalking, which had not been front page news since the murder of Priyadarshini Mattoo in 1996, was stirring conversations. Over the next few weeks, a spate of murders and attacks by stalkers made headlines.

In Tamil Nadu and Pondicherry, there were two murders and two murder attempts between August 30 and 31. Sonali, a 20-year-old college student in Karur, was killed inside her classroom with a wooden club by her senior, Udayakumar.

Francina, a 24-year-old schoolteacher, was the victim of a murder-suicide in a church days before her wedding. Her attacker Keegan had been pursuing her for two years.

Monica from Tiruchirapalli was stabbed by a man whose proposal she had rejected. Hanodonis from Pondicherry had her wrists slashed by a stalker.

A few weeks earlier, a 17-year-old schoolgirl in Vizhupuram had been killed by 32-year-old Senthil, who broke into her home, set himself on fire, and then hugged her.

On September 14, Dhanya of Coimbatore was killed by Zahir, who attacked her with a knife when she was home alone.

On September 20, 28-year-old Laxmi was chased and stabbed in Inderpuri, Delhi, by her stalker Kumar, who killed himself after. In north Delhi, 22-year-old schoolteacher Karuna was stabbed nearly 30 times by a man on a bike. He turned out to be her neighbour Surender Singh, who had been harassing her for months. Both Laxmi and Karuna had filed police complaints. No action was taken in Laxmi’s case; questioned about Karuna, police told media the families had “reached a compromise” and the stalker had backed off—until the day he killed her.

Was stalking becoming a sudden problem, or was it being highlighted suddenly? The laws are in place. The Criminal Law (Amendment) Act of 2013, popularly called the “Nirbhaya Law” for the victim of the 2012 Delhi bus rape, had strengthened Section 354 of the Indian Penal Code (IPC), making stalking and voyeurism crimes in themselves. Why were women being attacked? Why were the police not able to stop their stalkers before they turned murderers? What makes someone with no criminal record attack a woman he purportedly loves, so brutally that she dies? What does someone who has been repeatedly rejected expect to hear when he confronts a woman with a weapon?

In their paper An

exploration of predatory behaviour in cyberspace: Towards a typology of

cyberstalkers, Leroy McFarlane and Paul Bocij classified cyberstalkers into

four types—vindictive, the most ferocious kind, who would not only

bombard their victims with messages, multimedia images, and threats, but hack

into their computers and usually expand their pursuit offline; composed,

whose aim was not to establish a relationship, but merely to cause annoyance,

irritation, and distress; intimate, keen to make their targets fall

in love with them or to “win” back exes; and collective, which

describes group stalking—in other words, trolling—of a person who has the gall

to have an opinion at variance with the collective’s. There have been various

classifications of stalkers in physical space.

While theory may divide stalkers into online and offline, neither police nor criminologists believe they are quite so distinct. Professor K Jaishankar, president, South Asian Society of Criminology and Victimology, put forward what he calls “Space transition theory”—he believes the laxity of laws governing cyberspace and the anonymity it provides allow people with a propensity for stalking to “export their repressed behaviour” from offline to online arenas.

“Cyberspace,” he told me, “is a transient space. People go there, but it’s not a dwelling place. The moment you switch off your computer, you come back to reality. But what you do there affects you in a physical way where the pain is real. When you lose money from your bank account through phishing, your loss is real. When we do something online, people may think it is happening in an unreal situation, but cyberspace is only a medium between two people interacting; and they don’t understand that this is happening in physical space.”

The transition from cyberstalking to physical stalking is only natural and exacerbated by the fact that people are inclined to be less cautious in cyberspace, unconsciously encouraging a prospective stalker’s dreams of reciprocity.

Jaishankar says, “We live in flats where we don’t know the neighbour’s name, where he’s working. But in a train we try to become friends with the neighbour. How are we able to develop that relationship? The environment is not constrained. It is a light environment. So people tend to reveal more of their interests. The same thing happens in cyberspace. As in the train, we don’t know if this person is good or bad. Just because they are travelling with us, we try to accommodate that person.” Facebook, he said, gives people the same illusion of safety. People welcome others into their lives, and virtually take them into their homes, offices, and circles of friends and acquaintances.

The victims to whom I spoke were pursued by men whose relationships and intentions varied—some were ex-boyfriends; some strangers whose identities they never discovered; some were haters who only sought to destroy and instil fear. But they had some things in common—stalking spilled across modes of communication; in many cases, the stalker had female accomplices; they did not go to the police.

Every woman to whom I spoke asked me the same question: “You’ve been stalked, too, right?”, or said matter-of-factly, “Obviously we’ve all been stalked at some point.”

“My stalker was an ex-boyfriend who turned sour when I called our relationship off,” said Deepa Prasad*, a mother of two in the National Capital Region, “We dated for eight months, and after we broke up, I decided on an arranged marriage. I think that was the trigger—he felt I had dropped him and chosen someone else, though that’s absolutely no justification.”

It was scary that he knew where my in-laws lived. He claimed he was coincidentally visiting a friend in the same complex, but I’m sure he followed us. I was sitting with my in-laws, terrified he would land up and do something nasty. It was psychotic.

The stalking began in March 2009, when she got engaged, and continued past the new year. “He would be lurking everywhere. On our Thalai Deepavali (the first as a married couple, when the groom visits his in-laws), he smashed my husband’s car. Only I knew who was behind it. I was afraid telling my husband would shake the boat, so I let him think it was some rowdy. The next morning, we went to my in-laws’ place and I found the guy standing outside. I freaked out. I was shaking, I had no clue how he was there. He started texting me, saying things like, ‘How can you be happy?’

“It was scary that he knew where my in-laws lived. He claimed he was coincidentally visiting a friend in the same complex, but I’m sure he followed us. I was sitting with my in-laws, terrified he would land up and do something nasty. It was psychotic.”

“For the longest time I was scared to go out,” she said, “What if I saw him and he saw me happy? We lived in Bengaluru then. I hated coming to Chennai because of the fear.”

She could not bring herself to involve her family. Her husband only knows fragments of the story, but they have not had a conversation about it. “My husband saw me getting out of the car, saw how I froze and just stood there.” He knew something was wrong, but did not ask, perhaps sensing that she was not ready to tell him.

The obsessive pursuit waned only when her ex’s parents insisted that he get married.

“So he’s married now?” I asked.

“Yes,” she said, “He is father to a girl as well. How do I know? He texts once in a while. He has apologised for all that happened as well. Do I forgive? I’m not sure.”

Another woman who did

not want any details revealed told me she had quit social media, changed her

phone number numerous times, changed jobs, and moved cities. She even insisted

to her boyfriend that they move abroad after marriage because she was sure she

could not live in peace in India.

“It’s not that I don’t want to be on Facebook,” she told me, “I used to be crazy about social networking. I’d go on vacation, come back to office and upload directly from my camera to Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, you name it. That bastard changed my life. I got so paranoid. Not a single photo of my wedding is up online. I told my fiancé not to upload them either. This asshole went to my parents and told them I was dating a womaniser and that they should get me married to him. He just landed up at our house. Can you believe it?”

Her parents went to meet the stalker’s parents to persuade him to stop. “His mother actually said he’s depressed because of her, why can’t she talk to him. That was their reaction,” she said.

Why did she not go to the police? Why do women hesitate to file a report? The popular theory is that a police case could lead to societal stigma. The victims have a more pragmatic reason—fear of retaliation.

On November 14, 2012, 23-year-old Vinodhini was doused with nitric acid in Karaikkal by Suresh Kumar. He had been stalking her, and her family had filed a police complaint. Enraged, he decided to kill her. Vinodhini was in hospital for nearly three months in Chennai; she died on February 12, 2013.

On July 16, 2015, Meenakshi was stabbed multiple times by Jai Prakash, his brother, and mother, in Anand Parbat area of New Delhi. She had complained of his advances to police in 2013. As a result, he and his mother had been taken into preventive custody. Her family told the media Jai Prakash’s family had been pressuring them to withdraw the complaint. She eventually died of her wounds.

Ramkumar, on the other

hand, decided Swathi—who once threatened to complain to the police—must be in

love with him if she had not registered a case.

What, then, must women do?

A senior police

officer involved in the Swathi investigation said, “If there is danger, please

report. Nowadays we are very strict about it. We will take action. If you keep

quiet, the other person gets emboldened. But once he knows he is in the police

radar, he will restrain himself. After all, these people are not hardened

criminals.”

“Police are corrupt. And they are insensitive to the new laws,” said advocate B. S. Ajeetha, “It is hard enough to file an FIR. When the person is politically influential—he need not be a minister’s son, he could be the driver—forget about it. If the victim wields power, their efforts will be different. When it comes to Dalits, tribal communities, the poorest of the poor, we know what happens.”

I asked a sub-inspector in Chennai how the police usually deal with complaints of stalking.

“We try to nip it in the bud. Our aim is to make it stop. You know who comes and complains boldly to us? Women from places like Vyasarpadi, MKB Nagar, Puduvannarapettai (localities in north Chennai considered hotbeds of crime). The trials are ongoing. We follow up. There is no retaliation. The best way to ensure that someone is put away is to see it through.

We try to nip it in the bud. Our aim is to make it stop. You know who comes and complains boldly to us? Women from places like Vyasarpadi, MKB Nagar, Puduvannarapettai (localities in north Chennai considered hotbeds of crime).

“But we do have women asking us to be discreet. And we understand. We also have families. People are okay with a man filing a complaint, or if he has a girlfriend, but when a woman files a complaint, they view her with suspicion even if she has had nothing to do with the guy. And if the stalker is a former boyfriend, the family simply wants it to stop. We can’t insist that the law is set in stone. Does the law give space for anbu (affection), for gauravam (honour), for nambikkai (trust)?”

Prasanna Gettu,

founder and CEO of the International Foundation for Crime Prevention and Victim

Care (PCVC), Chennai, weighed her answer when I asked about the police

attitude. “I think they get no training on stalking. We did a study 3-4

years back with college students. During focus group discussions, almost 90 per

cent of girls from colleges in Chennai said they’d been stalked and sexually

harassed—the person got on the bus at their stop, got off at the college, and

it was torture.

“When we told them there are women police at the bus stops, they said a constable replied, ‘Pasanga-naa appadi dhaan ma iruppaanga. Neenga dhaan adjust panni ponum. (Boys will be boys. You must learn to adjust.) That is college life.’ That’s what they call it, college life.”

Some students reported that when they insisted on filing complaints, the first question was how they responded. Had they smiled or giggled? Had they encouraged the alleged stalker in any way?

“A girl may giggle at unwanted attention because she is not sure how to respond,” Prasanna said.

PCVC has been liaising

with the police for 15 years. Prasanna wishes they would not think for the

victim. “Say a woman comes straight from ICU. She could have stitches, but if

it’s the husband who’s beaten her up, they still try to patch things up. With

stalking, they recommend that you leave it to them to warn or threaten the

offender. An FIR is never filed unless you insist.”

The cynical might attribute the reluctance to file an FIR to the police avoiding a heavier workload. Prasanna does not believe that. They may have good intentions but it does not necessarily work out for the petitioner.

“With every crime against women, I think if the police go by the book, it would be more effective. If the person gets off with a warning, it is not a deterrent. Police personnel themselves say things like, ‘We can file a case, madam, but look at it from their perspective. Tomorrow, if her marriage is fixed, her groom will ask who this boy was, he will suspect she had an affair’. Just go by the book, saying my role is to look at the complaint and act on it.”

Many victims of stalking, especially in college, don’t report it not from mistrust of police, but fear of their families’ reaction.

That was why Laxmi,

now a model, television personality, activist and entrepreneur, chose silence

in 2005. “I was scared. But I did not tell people at home. I was 15. He was 32.

It was his word against mine. Even if they believed me, I was afraid they would

stop my education.”

He was Naeem Khan alias Guddu, who worked in her New Delhi neighbourhood. He got to know her family well. “I used to call him bhaiyya. I had no idea he had started falling in love with me.” He proposed marriage in 2004. She turned him down. He threatened her every day for ten months. Then, on April 22, 2005, as Laxmi was walking through Hanuman Road to Khan Market, a motorcycle stopped and the pillion rider, a woman, threw acid on her. Laxmi was rushed to hospital with 25 per cent burns on face, arms and chest. Investigations revealed that her attackers were Khan and his friend Rakhi. He was convicted and sentenced to 10 years’ rigorous imprisonment; Rakhi to seven.

Since her attack, Laxmi has successfully campaigned for regulation of the sale of acid, and for acid attacks to be recognised as a separate crime in the IPC. She has won international recognition and awards, meeting several heads of state including the Obamas. She has also found love—with activist Alok Dixit; they have a daughter, Pihu.

Laxmi and Alok run the NGO Stop Acid Attacks, and Laxmi started Chhanv Foundation to help victims of acid attacks. Three years ago, they founded Sheroes Hangout, a chain of cafés employing acid attack survivors. Medical treatment wipes out the savings of most families of survivors. And then, Laxmi said, no one will give victims a job, “Kyun ki hamara chehra kharaab hai (because our faces are ruined).” The first outlet of Sheroes Hangout was inaugurated in Agra. They now have cafés in Lucknow and Udaipur. Their flagship store brings in about 500 customers a day.

“People need to know what happens after an acid attack. So we talk to customers about our lives. They will know what problems we face, and maybe offer other survivors jobs,” Laxmi said, “Society treats you so horribly. People don’t want you in their sight. They used to pass such ugly comments. Like, ‘aage se dekho, kitni buri lagti hai; peeche se dekho, kitni achhi lagti hai. (How awful she looks from the front, how lovely from behind.)’ They would ask me to cover my face. Am I the criminal here? As for him, the first thing he did after getting bail was to marry. I would wonder who’d give their daughter to a man like this, a man who’s ruined the face, the life of another girl. Didn’t this woman feel any fear living with someone who committed such a heinous crime? But, when I used to go to court for hearings, his wife would accompany him, and she’d look at me as if I had committed a crime against her husband. This is the mentality of society.”

Official statistics on acid attacks were not available until 2013. Statistics compiled by several NGOs, including Acid Survivors Foundation India, Stop Acid Attacks, and Campaign and Struggle Against Acid Attacks on Women show that the prime motivations for acid violence are rejections of proposals, dowry demands, and suspicion of infidelity.

Professor Mangai

Natarajan, a gender crime specialist who teaches at the John Jay College of

Criminal Justice in New York, has done extensive research on street sexual

harassment and is currently researching acid attacks. She told me acid violence

was most common in South Asia, the Middle East, and Africa.

“Stalking does happen across the world” she said, “But families refuse to go to the police in India. The girl is alone, traumatised, distressed. Most women in the west are empowered to report, and when they do, police can enforce the law. There are places in India where if somebody rapes a girl, the elders try to get him married to her to protect her chastity and the family’s reputation. The same thing goes for acid attacks—there are cases where women have married people who threatened them with acid violence unless they accepted their proposal. What sort of life will she have? We need to empower women not to be fearful of reporting threats. But we don’t know how to.”

Jaishankar feels the patriarchal structures in the value system of certain countries allow stalkers to rationalise their actions. “Even if the west is patriarchal, it is not in the same sense. Here, there is a preconceived notion that women are inferior,” he said. “That is fostered from childhood. If the boy in the house wants a sweet, his mother and grandmother make it right away. He is prioritised over his sister, because she will go off to another house, whereas he is the one who will transmit the genes to the next generation. So when he likes a girl, he thinks of her as the sweet—and when she rejects him, his ego cannot handle it. He wants to destroy her by taking her beauty with acid, or her life.”

In 2002, Bangladesh had the highest rate of acid violence against women. The same year, the Acid Control Act was passed, regulating its sale and increasing jail terms for acid possession as well as violence. The number of attacks fell from 494 in 2002 to 36 in 2016 (Acid Survivors Foundation).

India, too, has put laws in place.

The Criminal Law (Amendment) Act, 2013, in addition to strengthening Section 354, inserted two sections under 326 (Voluntarily causing grievous hurt by dangerous weapons or means), which made attacking someone with acid (326A) and attempting to do so (326B) cognisable offences.

Supreme Court advocate

Karuna Nundy was among those who represented human rights and women’s groups

before the government while drafting the Criminal Law (Amendment) Bill 2013.

She pointed out three loopholes in Section 354(D)—(a) ease in getting bail; (b)

the ineffectiveness of witness protection programmes; (c) the gender

specificity of the law.

“The problem with 354(D) is that it is bailable till the first conviction. This is exceedingly silly,” she told me, “Stalking in any case is repeated following. And it’s repeated following with expression of disinterest (on the woman’s part); then, it has the potential to become dangerous. If there is an explicit threat, it is criminal intimidation. As we all know, there can be all sorts of veiled threats—somebody standing outside your house saying, ‘I love you, I can’t live without you. I will kill myself.’ It should be a non-bailable offence. And when we were working with the government, we said it should be non-bailable in the first instance. That does not mean you don’t get bail, but it’s at the discretion of the judge. The judge can look at the circumstances, the level of threat and then decide.”

When the case is being heard, witnesses often either back away or change their stories. Nundy said most states don’t have the resources to protect witnesses. When even victims are worried about retaliation, few witnesses would choose justice for another over personal safety.

Where the LGBTQ community is concerned, there are vast lacunae. Nundy said the only recourse gay men and transpeople have even to file a complaint of rape is Section 377, which does not differentiate between consent and non-consent.

“A lot of transgender people are raped or assaulted. You also have men who are raped and assaulted. So how can you not have a remedy for that? It’s crazy. The agreement was that the victim must be gender neutral, phrased as ‘person’ and not ‘woman’. I don’t think it was mala fide on the part of the government, more a misunderstanding; and it was not phrased that way.”

Nirangal, a

Chennai-based non-profit organisation for advancing rights and justice

for people with alternate gender and sexual identities, is involved in

crisis intervention and providing legal aid. I spoke to team members Siva Kumar

and Delfina about whether the provisions under 354(D) have actually helped—or

can help—the LGBTQ community.

The Supreme Court’s judgment in the National Legal Services Authority vs Union of India case reads: “Transgender persons’ right to decide their self-identified gender is also upheld and the Centre and State Governments are directed to grant legal recognition of their gender identity such as male, female or as third gender.” Technically, transwomen who are stalked can file a case under Section 354(D). However, this does not happen. For one, though the judgment was delivered on April 15, 2014, it has not been implemented.

Delfina said, “I think for transwomen being stalked has become the norm. It is obvious injustice, but they have gone through so much injustice that they have either become desensitised or feel that it’s not feasible to take up every single fight.”

The case of gay men is complicated by the fact that they are stalked less by strangers than by exes or acquaintances. In some cases, they may have had a sexual encounter with someone they met on dating apps like Grindr, only to be blackmailed or threatened. Most gay men who approach Nirangal are closeted. They don’t want to involve police even if there’s a case for criminal intimidation, because they are worried that their sexual orientation may be made public.

An activist to whom I spoke, whose identity is being protected, told me about an extortion ring. Often, members of gangs pose as homosexual on dating websites. They fix a meeting point and by persuasion or deception record photographic or videographic evidence of their victim’s sexual orientation. They then extort them for money, jewellery, and so forth. In one case, a man was forced to order an air-conditioner on his credit card and have it delivered and installed at the home of his blackmailer.

Siva Kumar said it was impossible for gay men to register most complaints. “Going to the police is very difficult because legal action will incriminate him under Section 377. We usually advise counselling for the victim. Then, our only option is negotiation.”

When I asked a senior police officer about the law for men who are being stalked, he was discomfited. “I don’t think I can say anything about that. Stalking is mainly on women, right? Normally laws are for the majority of cases. Exceptions may not be covered.”

When the laws don’t make allowance for a crime, it cannot be considered a crime. Delfina said, “By and large, we haven’t seen a specific homophobic bias in the police. But there is lack of understanding, lack of sensitivity. There are misunderstandings about Section 377.” Transwomen may be benefited by the National Legal Services Authority vs Union of India verdict, but only after the rights conferred by the judgment are actualised by the government.

Ajeetha sees problems

in the framing of laws, as well as their implementation.

“Take the Tamil Nadu Prohibition of Harassment of Women Act—it does not cover ‘stalking’ or ‘following’. Somebody silently coming behind you would in a strict sense not come under the purview of that Act. Then there is burden of proof; someone who is not a relative should say yes, he stalked her. While the case is on, they can always offer you something to withdraw it. If you do not listen, they will send it to remediation. Or it can come to High Court for quashing of the case because certain cases are not compoundable.”

In Tamil Nadu, the Tamil Nadu Prohibition of Harassment of Women Act, 1998 is preferred to Section 354(D), especially when the stalking has resulted in a more severe crime, such as physical assault or molestation. This law, which was enacted after the death of Sarika Shah (who was killed in an accident while trying to escape two men who were sexually harassing her), carries a maximum term of 10 years and a fine of Rs. 25,000, as opposed to Section 354(D), which carries a 3-5 year jail term and a fine of Rs. 10,000.

Ria Sharma, founder of Make Love Not Scars, which provides medical aid, legal resources and counselling to victims, said, “Acid violence is an easy crime to commit because it is so readily available, at 30 rupees a litre. It’s much harder to procure a gun, harder to shoot someone, because there’s bloodshed, there’s chaos. With acid, it’s like throwing water on someone. And when you see that the penalty is only a few years in jail whereas the woman spends the rest of her life as a living corpse, it encourages the perpetrator.”

A Supreme Court order in 2013 on a petition filed by Laxmi banned over-the-counter sale of acid without photocopying a government-issued photo identity card and recording the purpose of the purchase.

It also banned the sale of acid to minors, and said undeclared stocks of acid would be confiscated and the seller fined up to Rs. 50,000. In the same order, compensation for victims was raised to Rs. 3 lakh—the state was required to deposit Rs. 1 lakh within 15 days of the attack, and the remainder within two months.

Stop Acid Attacks is conducting a campaign, #ShootAcid. Its volunteers were in Kanpur, where four acid attacks had been carried out in September.

“We’re sending people to shops to buy acid, and we’re shooting it. Shops are not following the order. I myself bought acid. Hum log bas ye hi bolte ki tezaab de deejiye. De dete hain, aaram se (We just say ‘Give us acid’. They hand it over). They don’t have licences to sell acid. But not a single shopkeeper said ‘We don’t have it’ or ‘We can’t sell it’. So I asked them why they stock it. All of them said the wholesale dealers bring it. I asked if they were aware of the Supreme Court order. They said they were, and then they said, ‘Go ask that guy, he’s also selling it.’ Finally, we managed to persuade all of them to stop stocking acid without licences. And they also gave us the number of the person who comes to sell acid. We have filed an RTI.”

I spoke to Laxmi the day after a special court in Mumbai sentenced the accused in the Preeti Rathi acid attack case to death. She was upset the case had dragged on for three years. It took police two years to find the culprit. Rathi’s father has been making repeated trips to Mumbai from Delhi for the hearings.

Ujjwal Nikam, the public prosecutor handling the case, confirmed that the convict—Ankur Panwar—had taunted Preeti Rathi’s family in court, provoking a fistfight. Panwar was also photographed showing the victory sign to cameras. Nikam said Panwar purchased 2.5 litres of sulphuric acid from a shop in Delhi, after Preeti repeatedly rejected his proposals. She was selected as a lieutenant in the Indian Navy Nursing Hospital in Mumbai. She took the train from Delhi to Mumbai with her father and uncle on May 1, 2013.

“The accused was secretly following her in the same train,” Nikam said, “When Preeti and her family got down at Bandra station on May 2, about 8.15 a.m., Ankur also alighted and threw sulphuric acid on her face. Her lungs were damaged, vision was lost. Her windpipe and food pipe were also damaged. Blood was oozing from the intestine. And she died in agony on June 2, 2013.”

He added, “He will definitely appeal. Let us pray this verdict is upheld in the High Court and the Supreme Court.”

If physical stalking

is hard to curtail, cyberstalking is worse. In June, 21-year-old Vinupriya

lodged a complaint after morphed photographs of her were put up on Facebook.

They were still up when she committed suicide, six days later. She wrote in a

note that she had not sent nude photographs to anyone and begged her parents to

believe her.

The laws governing abuse on social media are usually American. A police officer at the cyber crime cell told me that court orders might be needed for the internet service provider (ISP) to intervene.

Even if police do genuinely want to help a victim, the laws can be a hindrance. A senior police officer based in Hyderabad told me one often has to find ways of working around the law.

“Recently, we were approached by a single mother—a widow—who is crying and crying. She said ‘One boy is there from my daughter’s college, continuously troubling her to have relationship with him for last four years.’ She is having some shop. The boy is coming to buy small items and smiling at the daughter. This lady told the boy to stop coming, and he said ‘What is your problem, I am just buying a notebook’ and such things. Then she mentioned her daughter and the boy said ‘I love her, you’re having doubts about me because I don’t have a job. I will get a job and come back.’ Then silence for one and a half years. Suddenly, one day, he has come back to the shop and said, ‘I have a job, I know your daughter is working in such-and-such company in such-and-such city. I came for your blessings to marry her.’ In such a case, what are we to do? What provisions are there in the law to deal with him? The media is reporting, we are filing false cases or we are letting off with a warning. I can only say we do what we can to ensure the crime stops.”

Looking through case judgments across the country, it appears 354(D) is usually used in concert with other offences to build a stronger case and enhance punishment. In the rare cases where it was the only section under which the accused is tried, they were acquitted.

Even if a man is convicted, he will be out in three years. Laxmi’s attacker Naeem Khan will be released this year. Ten years seems a long time, until the ten years are up.

Several initiatives

have been taken by the Tamil Nadu police, such as the citizen’s portal and

mobile app to file online complaints.

Superintendent of Police for Tirunelveli, V. Vikraman, introduced a service, “Hello Police”, for people to send complaints anonymously through text messaging, WhatsApp, or phone to the number +919952740740. The dedicated control room would be next to his chamber and he guaranteed immediate action. From images of suspects to bike registration numbers, reports flooded in. The service was activated on March 21, 2015. From that date to October 13, 2016, 3,217 complaints had been received and 513 FIRs registered, with 1,151 accused. But it did not have much effect in deterring crime against women, especially stalking.

“When you grow up in a city, it’s hard to grasp the mentality of people in a place like this,” Vikraman said. “You have husbands running away with other women, and when the wives come to us, they’re not looking to register cases. They simply want us to get their jewellery back. A lot of girls are afraid to tell their parents they’re being followed. They will either stop their education or get them married off because that’s their idea of a solution for stalking.”

Vikraman had self-addressed postcards distributed in schools and colleges. Girls as young as ninth and tenth standard students began sending in complaints. “One girl drew a map to the place where her harasser worked,” Vikraman said, “We’ve had complaints about lab assistants, teachers, about other people who follow them.”

A self-confessed

stalker volunteered to talk to me. Komal Som* had stalked the wife of a

colleague with whom she was having an affair. Her story changed slightly every

time I spoke to her. Sometimes, she was defensive, at other times she spoke

about her actions as if they were those of someone else, with extreme distaste.

“My shrink says one of the steps is admission,” she told me, “That’s why I’m admitting it. I’m a stalker.”

She hacked into his email, “temporarily stole” his phone and checked text messages, read his exchanges with his wife, and even tried to hack into her email.

“I was seeing a man from my office. He was married. But his marriage was on rocks, okay?” she said [sic.], “He wanted to leave her, but she threatened suicide. That’s why I decided to take matters into my own hands. If she found out about the affair maybe she would break up of her own accord and things could be worked out.”

The affair began when they were on the same shift—Komal would “bitch about [her] ex-husband”, and he would speak about problems with his wife.

“We made out in his house, we had sex on his bed, and he would say I should have his child. He wanted children, she did not. He gave me his email password and said I could check their conversations. But that night, he changed his password.”

In one of our earlier conversations, Komal had hacked into his email after observing him type his password. But she logged in from her own computer, and he must have received an alert, she said. In subsequent conversations, he had given her the first password.

Stalking his wife began online. “It started with checking his Facebook. She would comment on his posts and he would ‘like’ those, and she would randomly tag him in things. She was posting all these pictures, and he had to ‘like’ them. And when a couple is giving like full-on PDA, you know something is wrong, na? I even confronted him, and he was like she’ll make me log in and ‘like’ this. And I was like how controlling can this bitch be? I’d be looking through her comments on friends’ posts, what she ‘liked’ etc. She would keep using Foursquare and Check-In, so I was often tempted to go to those places. Sometimes, she would check him in with her, and I wanted to see how they behaved as a couple.”

Eventually, she noticed that the wife had joined a gym. She decided to meet her there. In one version of events, she said she didn’t know why it was important to meet her. Then, she came up with reasons—“I just wanted to see her as a person”; “I wanted to establish that I knew him and maybe put a seed of suspicion in her head”; “I wanted to make friends with her and see if she bitched about him. Then I could say he’s an asshole, leave him.”

The first few days, they did not meet. “So I took leave for a week, and went to the gym. Once I spent four hours working out. Finally, one day I saw her. I found out approximately when she comes there. I adjusted my shift and used to go every day around that time. Eventually we got talking. It was the usual conversation, where do you work etc. etc. She told me her husband worked there, and I asked for his name. She told me. I said, ‘Oh, I didn’t know he was married; I thought he’s dating someone in our office.’ She looked startled. Then I panicked, and said which branch, and pretended I was in a different one. She seemed immediately relieved.”

Eventually, Komal followed her to malls and meetings with friends. She staked out the house on weekends. She did “observe them as a couple” and is confident there were problems. It became an obsession. Every waking moment she was not in office, she would be in pursuit. She would will the wife dead, she said, though she did not “actively” do anything to ensure it.

“It was raining really hard in Delhi one day; you know, one of those rains where the whole city is paralysed. And I was driving from Gurgaon to this gym in Saket, and I’m crying and sitting in the car and thought how pathetic am I that I am going all this way to just see this woman and her husband doesn’t even care enough to commit to me. So I called him from the car itself and told him you have to tell her or I will tell her.” They had a fight, at the end of which she called the wife (whose number she had saved when she had “temporarily stolen” his phone).

The wife and he are now separated, Komal said. But he is not with Komal either. Once she told me she had got so angry she had stopped taking his calls; another time, she said it was he who had cut off contact.

What drives someone to

stalking, to learn another’s routines, to harass or threaten them? It is

commonly believed they have some form of mental illness. In the case of

Ramkumar, three police officers who interacted with him said he “seemed off”.

Dr. S. Mohan Raj, consultant psychiatrist in Chennai, says the problem is not

psychiatric; it is behavioural. There is not enough information to comment on

the Ramkumar case, he said, but most cases of stalking originate from

personality traits.

Some people, he said, simply cannot take no for an answer. The reasons vary. The question of mental illness arises only when the stalker is delusional. “We call this de Clérambault’s syndrome. The most common cases were of people convinced someone was in love with them. Invariably, in all well-known cases both here and abroad, it is a celebrity. It could be an actor, a sportsman, and these people go on following them. They have this fixed delusion that this person is in love with me, but not able to make it public because of social position. So they will gatecrash and then wonder why they are being thrown out. They misinterpret a photograph or video saying, ‘Oh, that hand movement was for me’.”

Even in such cases, the person cannot avoid responsibility for the crime he committed. Laws, in India at least, make little allowance for it.

It is hard to pinpoint a motive for behavioural stalking, Mohan Raj said. The stalker may do it from purported love, or envy. In the former case, they try to hound the target into reciprocation; in the latter case, the intention is to intimidate and harass. They could impersonate the person to defame him or her. In the case of unrequited love, they could turn angry at the rejection and avenge themselves.

Can behavioural stalking be treated? Mohan Raj says a stalker is unlikely to seek help. The first step is to accept that there is something wrong with his or her behaviour; in most cases, the stalker will not.

There are several petitions, online as well as in the courts, at the moment to ban positive reinforcement of stalking in movies.

It has not been proved that movies encourage stalking, but Mohan Raj said constant normalisation of what would legally be classified as eve teasing or sexual harassment or stalking could instil the idea that persistence would be rewarded.

Jaishankar has an even scarier theory: “In the movies, as long as he is pursuing the woman, she is independent and he’s crazy about her. But the moment his pursuit is over, he goes back to work and she becomes the housewife, even if she’s a very rich man’s daughter. His role becomes active in the main story, hers becomes dormant. So the movie shows this is only a small part in his life.” On the one hand, it is frustrating that this “small part” is taking up so much time and energy; worse, it may not strike him that disposing of this “small part”—attacking her or killing her—has actual legal and social consequences.

“Every hero can be put behind bars under stalking section of IPC in letter and spirit,” Ajeetha said. But is the converse true—can someone argue that a crime was heroic?

There is a case of an Indian security guard in Australia avoiding conviction for stalking by blaming the movies. Sandesh Baliga, 32, was accused of texting, calling, and following two women in 2012 and 2013. His lawyer argued it was “quite normal behaviour” for Indian men to chase women who showed no interest in their overtures and produced Baliga’s favourite movies as evidence. The magistrate adjourned the complaint for five years on condition of good behaviour.

Seema Agrawal, ADGP in charge of the State Crime Records Bureau in Tamil Nadu, showed me the statistics for violence against women. Most such crimes were committed by rejected suitors. “We advise our girls to be careful,” she said, “But do we advise our boys to be respectful? How can you transgress into the criminal realm when you claim to be in love with someone? It is this misplaced notion of manliness. Love is respect for the other person’s sentiments—not causing a nuisance, pursuing, stalking.”

Stalking is not always

a reaction to “love failure”. It could be the result of unadulterated hate.

Amala Sathish* told me her story of nine years of harassment by a college

classmate.

It began in 2005. Amala had been accepted into a course and found that she was not particularly popular in class. She believes it was because English was her first language, and for her caste.

“After the first semester, things started getting weird with this one chap, who made it like his personal vendetta. He would show up in the first row when I was making presentations and stare at me, making filthy gestures. I took it up with a teacher. She was sympathetic. She sat him down and said ‘This is not done; you can’t be doing this outside university, forget within. Do you have a problem? Let’s sit down and discuss it.’ He said she’s crossing her limits, a Brahmin woman crossing her limits, so the teacher said she’s not harming you, why don’t we just live and let live, and he sort of figured out the right way to quell her fears about it. She was convinced he had changed his stand. For about a week, he didn’t give me any trouble.”

She was stopped by a group of women from her college as she was about to head home one day. “One girl punches me in the stomach and I go flying. I’m winded and I ram my back against the wall. Then, [another girl] reached out and pulled my braces out, with her bare hands, and the entire lip was cut. She punched me on the nose, the break you can still see here”—she pointed—“I believe she punched me on the nose, although the guy who stalked me claims he punched my nose. I blanked out after a point, so I don’t know.”

Amala told her parents and they tried to approach the dean. But no witness was willing to testify to the attack. Then, she said, he began to follow her around campus with a cigarette lighter. First, he would burn holes in her dupatta.

“Once I turned round and asked him what his problem was and he said next time, you’ll be burnt and dead. So I confronted him, very foolishly so, and asked why he was doing this to me. He threw himself on me—there were only men around; the women walked away, they probably did not want to see, I don’t know—and he starts groping me all over. Nobody comes to my rescue.

“In the end, they’re all giving him high-fives as though he’d accomplished something. I found myself shaking, not knowing what to do. It was a good ten minutes before I realised I had to leave. I am a survivor of child sexual abuse, I’ve survived 13 years of sexual abuse, which includes rape. I don’t know why I never told my parents...whether it was to cover up my foolishness for having confronted him, or just not wanting to scare them anymore, but I don’t know.”

She began to avoid college, showing up only to write exams.

“But he managed to sit in front of me for one exam, and when we were waiting for the invigilator to collect the paper, he turns around and blackens my entire first page. Apparently, you can’t submit the paper then. Thankfully, the invigilator fastened a new sheet on top and signed off on it, and I was allowed to submit it. We get out, and I feel a sharp punch on my lower back. I had this shooting pain from my lower back to my toes and I’m bending double and he’s holding a bunch of brass knuckles in his hands right up to my face saying the next time this will be in your eyes. There’s nobody by my side. There are people walking up and down. I’m bent double. I’m in pain. I’m silent. I’m frozen. I’m quiet.”

Their next encounter was at the annual prize-giving ceremony, to which Amala had brought her parents. “In a full crowd, he walks past me and shows a bunch of condoms, saying, ‘This is for later.’ I got up, I went and sat with my parents, and he’s staring at me throughout the ceremony. I told my parents this is what he’s done, let me get out of here. They brought the car around. I bent over, crawled out of the hall, just praying I would get out safe.”

She decided she would not go back to college, even if it meant she did not earn her degree.

“But he knew where I lived—he’d followed me every single day of college as I would find out later from auto drivers and the watchman. So, he began to camp out at my place. He would arrive in the afternoon, and spend the entire day outside my apartment, just watching, keeping an eye. I tried to go about my life. He was literally staked outside my house, following me everywhere. I’d step out to sign a courier, and he’d be there. I’d go to the pharmacy, and he’d be there. I just had to look over my shoulder and he would be there. I was losing it, I needed a therapist, so I started seeing a therapist. He would follow me there.

“Once I’d gone out with my mother, and when we come back, there’s a tiny canister outside my door. She opened it. Somehow it slipped, crashed on the ground; it was acid. So my mum is like who left acid here, some stupid servant, you know, we don’t think...”—she paused for some time and then resumed her narrative—“Open the door, we go in, we see a note has been slid inside, saying, ‘Did you see the acid? That’s going to be on your face the next time’.

“The next morning I woke up like I was normal, saying I’m going for a jog. My mum was paranoid, ‘Why are you going out, what if he’s there, with...[acid]?’ And I said, ‘Who, ma?’ I’d snapped. I completely dissociated with everything. Four years were completely blanked out. 2006 to 2010, I had wiped out.”

At this point, she stared out of the window of the coffee shop where we were sitting.

“Do you want to take a break, shall we stop here for now?” I asked.

She seemed to be making an effort to stay composed. Finally, she reached for a tissue. But her eyes were dry, and she twisted it in her hands. “It’s just...I haven’t spoken about this before. I didn’t think I ever would.”

The next time we spoke, she took up from where she had left off. She told me she could not remember a thing—she did not remember a single day of college, she could not answer basic questions about the subject she was studying, and she had no idea who this man her mother had mentioned was.

“My therapist said its dissociation, a coping mechanism when there’s high level stress. So she said, ‘We’re not going to let you remember anything, but you know you’re unsafe. You’re not going to put yourself in a place where you’re alone.’ So I had everyday instructions. I hate to reference this, but it was like Gajini, the movie. I used to have a notebook which would tell me these are your numbers, this is where you should not go, this is how you should not be.”

The therapy went on for ten months before her memory began to stir. And it took a toll on her.

“For almost a year, I put myself in solitary confinement, literally. Of course, family and friends would come, but I never went out of the house. I was so sure that if I set foot outside those four [walls]...not just my house, but my room. If I stepped out of that little, tiny space, all my predators were there, everybody from my childhood. I started having these panic attacks at night—I couldn’t sleep without the light on. If the AC was noisy, I couldn’t sleep. There were certain actors whose faces I couldn’t see on television. There were certain sounds, certain words I couldn’t hear without getting triggered. That version of me still scares me because it shows me how much I can be destroyed while still being alive.”

On one of her first forays out of her house, in 2012, her stalker followed her family to a bookstore, and brushed against her at the billing counter. He was back. Amala asked that the details of how she shook off her stalker be withheld. The last time she saw him was when he showed up at her doorstep one day.

“He rang the bell once, and obviously, no one thought it was he. So we opened the door, saw him, and slammed it shut. Then he went on ringing the bell, like a hundred and fifty times. He’s drunk and he’s holding a bottle. He breaks it on the step and starts screaming about how if he doesn’t kill me that day, he will kill himself. And then he started cutting himself with the bottle.”

Alerted by the commotion, someone had called the police. It was the last time she saw him, but she received “filthy emails” from him over the next two years, including morphed pictures.

“He’s not in custody now,” Amala said, quietly, “Every day, I worry that he will show up again. As I’m talking to you, I worry that he will recognise the story and come for me again.”

Hours after our first meeting, I got a text from Amala. She told me the first thing she had done after going home was to throw up. “But my therapist said it was expected.”

*Names have been changed to protect identities

(Published in the November 2016 edition of Fountain Ink.)