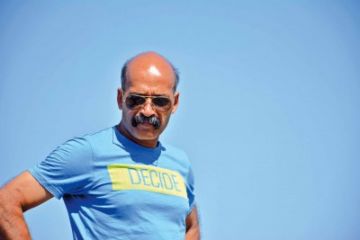

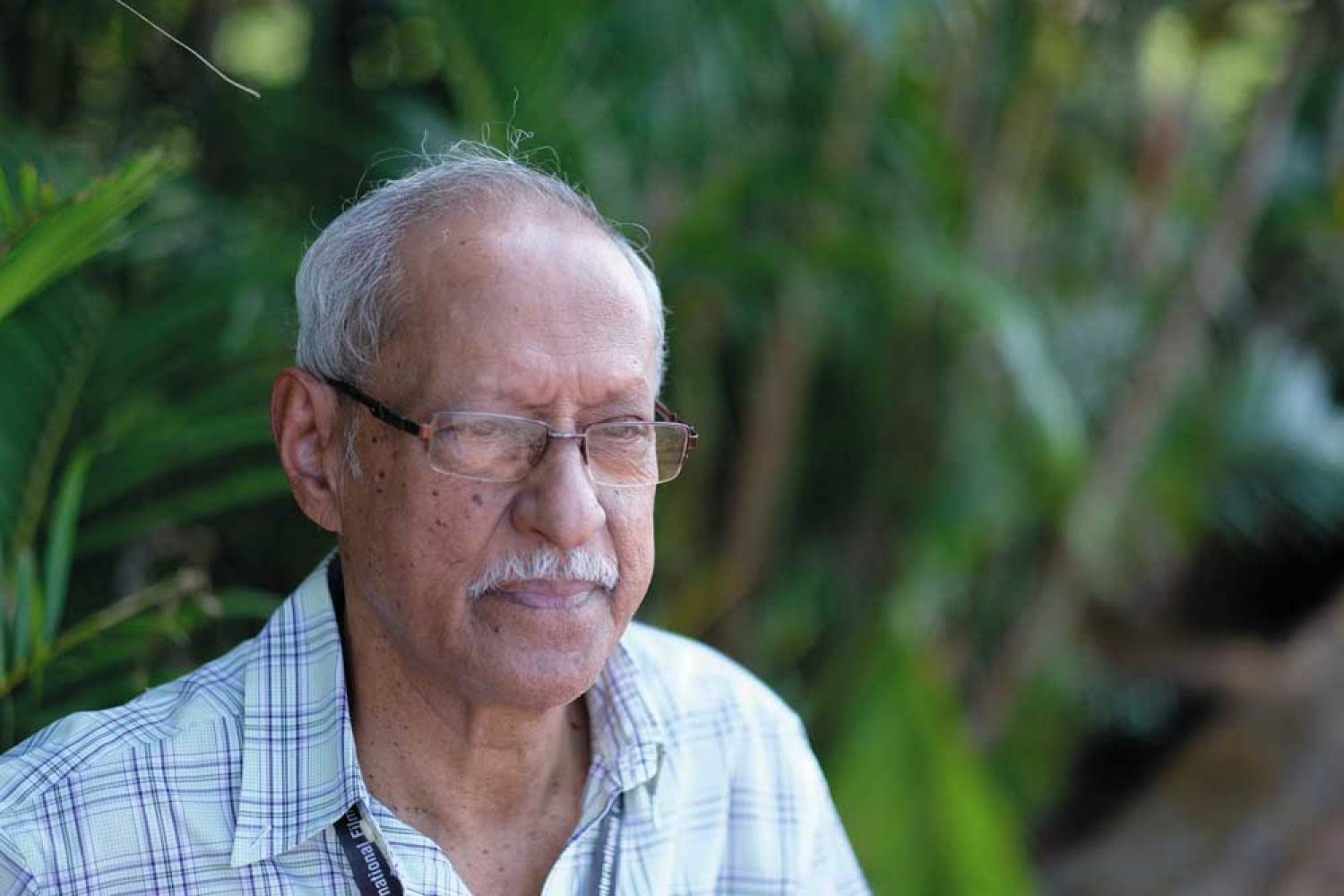

The phone keeps

ringing. Damodar Mauzo is taking a break after catching a 190-minute long

Turkish movie at the Kala Academy in Panaji as part of the International Film

Festival of India.

The short story writer

and novelist answers his phone. After a quick conversation in Konkani, he says

it was a newspaper wanting a quote on the farmers’ agitation in Delhi. Soon,

there is another call, this time about a press statement on the Sabiramala

agitation.

While Mauzo has been

writing