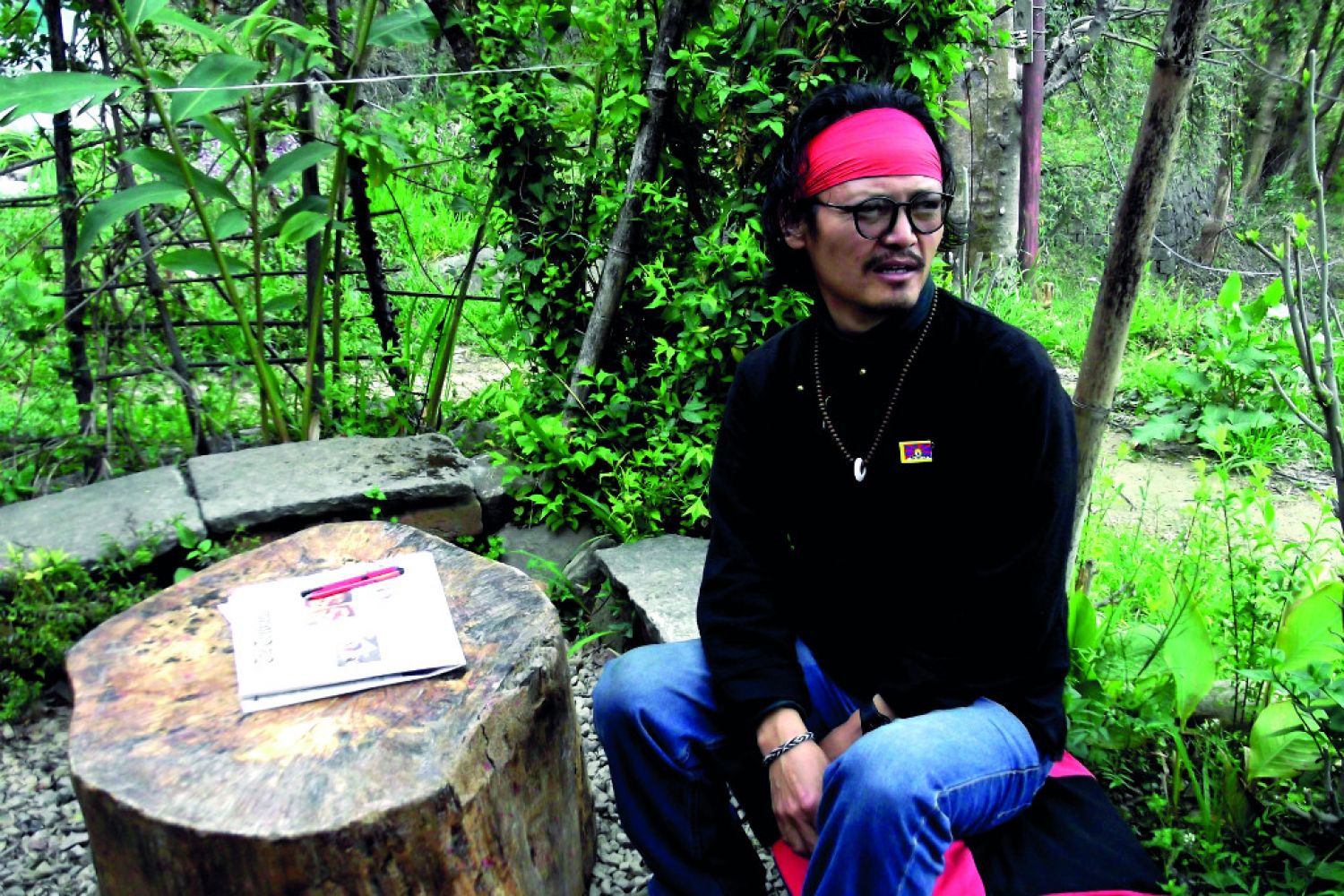

It is a picturesque

downhill trek from the Dalai Lama’s residence in McLeod Ganj to Tenzin

Tsundue’s house, a few metres uphill from the main bazaar of Dharamsala. The

poet, essayist and activist lives in one of the rented rooms of an almost

100-year-old British bungalow, exuding an old-world charm even in disrepair. He

calls it the Rangzen Ashram (rangzen meaning “freedom” in Tibetan).

Four other tenants live with him in the “ashram”.“The roof leaks,” he

says as he gi

Continue reading “‘Freedom struggle is my life’s meaning’”

Read this story with a subscription.