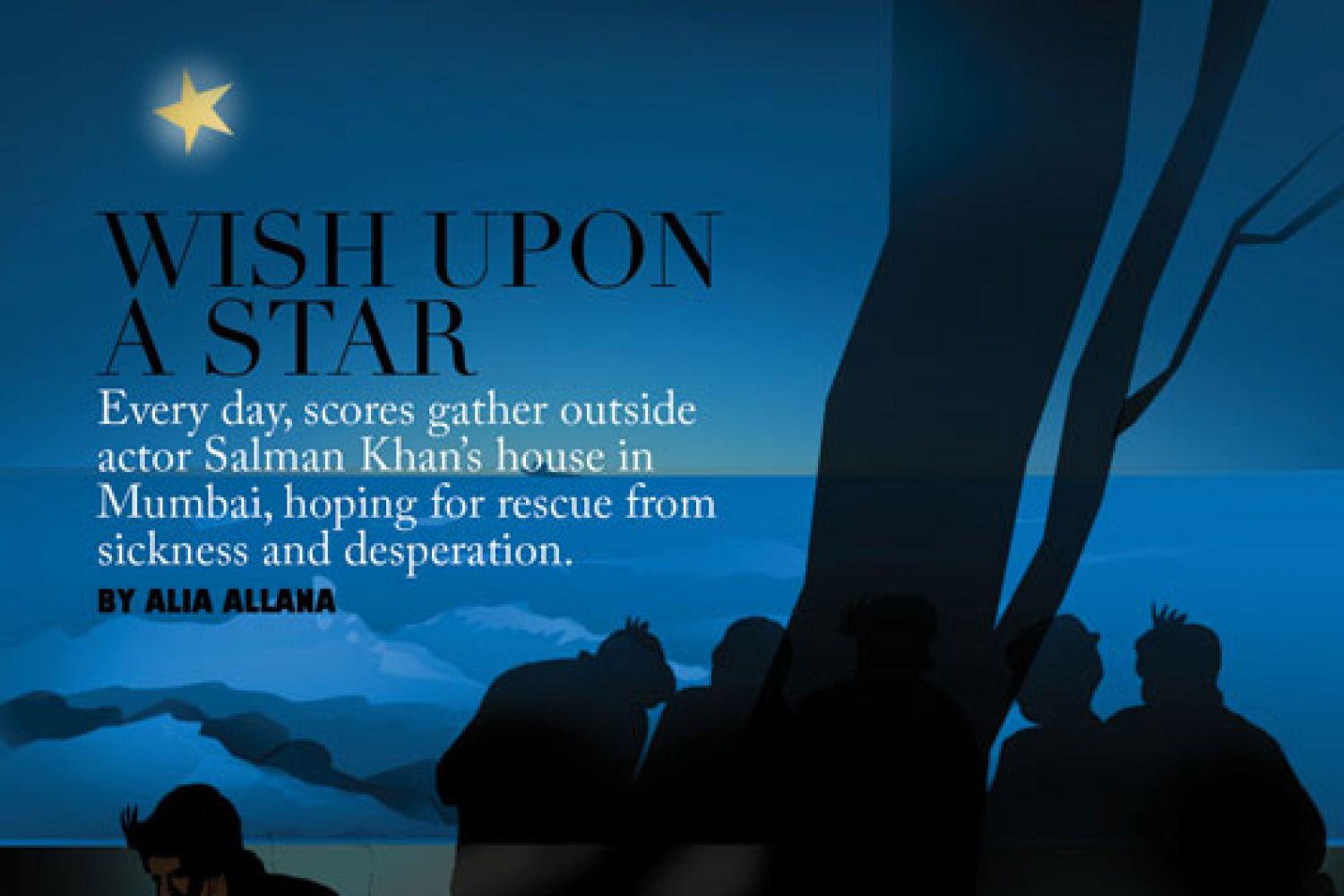

An auto rickshaw pulls

into the quiet curves of Bandra Bandstand. Streetlights illuminate the seafront

promenade, waves crash on the rocks below, but not a soul stirs.

Ratan Singh steps out

of the auto. He reaches into his pocket and pays the driver; they exchange a

few words. The driver points to a weathered white building that says Galaxy

Apartments. Ratan pulls his jacket shut and limps across the street. He sits on

a bench from where the patron of Galaxy Apartment, Salman Khan, might