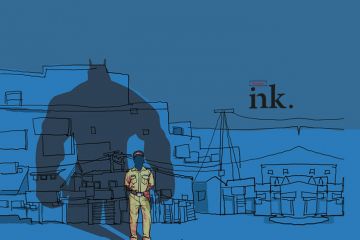

In an inner lane in

Lucknow where Kayasthas dominate a residential colony, Election Commission

officials are walking up and down looking for hoardings and banners of

political parties and ordering them to be taken down. The indigo graffiti of

the Bahujan Samaj party on the walls is not on their agenda yet. The graffiti

is for the candidate of the constituency, a Muslim better known as “Pandit ji”,

and who writes that useful epithet in brackets after his name.

Welcome to the Uttar

Pr