When Pinky saw an

unusually large crowd outside her room on the night of November 8, she was a

little startled. She peeped cautiously; the place is notorious for violent

crimes—assault, rape, gang rape, even murder.

Pinky is one of the

more than 30,000 sex workers who do business every night at Sonagachi in

Kolkata, Asia’s biggest and most crowded red-light area.

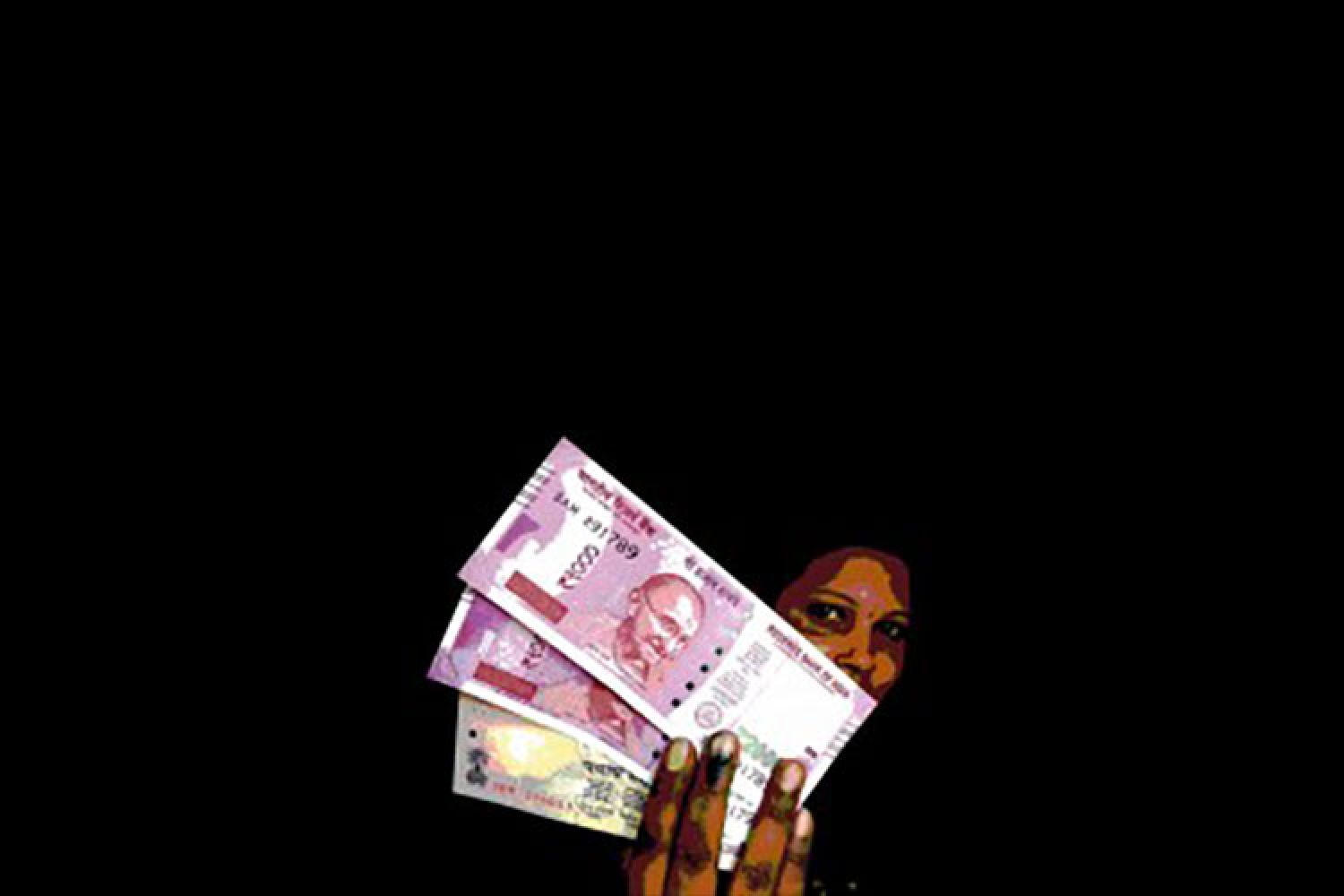

Then she saw her pimp

collecting money and seating people in a kind of first-come-first-served queue.

She recognised m